Why I Refuse to Take a Plea

There's more at stake in the Sonoma Rescue Trial than my freedom. It's a chance to show the world the power of open rescue.

What’s up this week

My co-defendant Priya Sawhney took a plea deal this week. I wrote more about what this means for me, and why I’m refusing to plea bargain, in the newsletter below.

Perdue Foods is facing a federal investigation for child labor, including a 13-year-old boy whose arm was mangled in the slaughterhouse machinery. This should come as no surprise to those of us who have seen how these industries ignore the cries of vulnerable beings.

Another journalist wrote to me last week with false allegations of various improprieties within DxE (the organization I co-founded and left in September 2019). Every few years, a journalist sends along these sorts of scandalous accusations, and I’m forced to respond. I have generally done so publicly, as I am doing in this case. Here are her questions, and my replies.

Open Rescue Advocates will be meeting in San Francicso on Sunday (today) at 5 pm. Priya will join us, to share her thoughts on taking a plea. I’ll be there briefly as well, to take a break from trial work — and offer what will likely be my last thoughts before our opening statements at trial. This is an invite-only meeting. See details here. (And don’t forget, if you’re already an ORA, join our Slack. That’s where our team is giving regular updates, including video recaps, on the trial.)

The Last Defendant in Sonoma County

For the first time since The Simple Heart launched in October 2021, I failed to blog last week. The reason, as many readers might have guessed, is that I am, to put it mildly, having a hard time keeping up, as I go to trial.

And things just got harder.

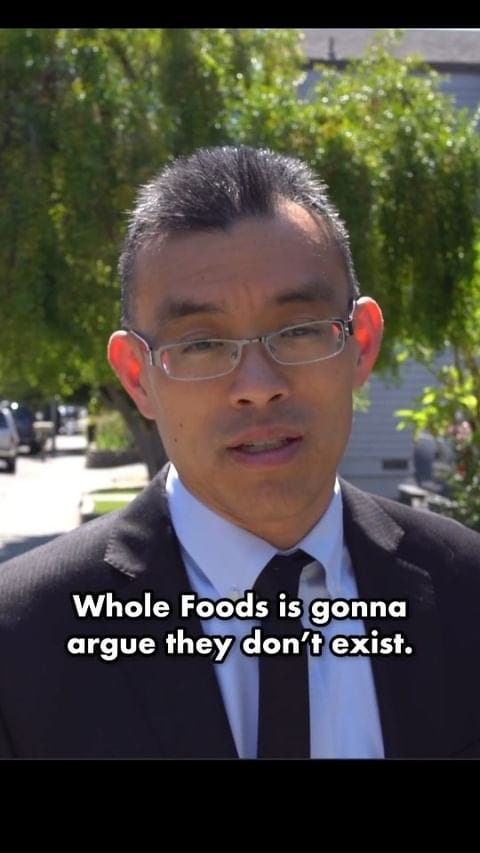

My co-defendant Priya Sawhney pled no contest on Thursday. In exchange for a commitment to stay away from certain local factory farms (among other terms), she will serve no prison time. It is the right decision for her. But I will now be the only defendant and lawyer against the combined might of the government, including two district attorneys working full time on this case; a half dozen corporate lawyers from companies like Costco and Whole Foods, who have moved to quash animal cruelty evidence from being presented in court; and a multi-billion dollar industry that has spent the last 10 years trying to destroy me (and, by extension, you). Sometimes, as I say in the video below, it’s felt like fighting a ghost.

But I am committed to fighting on.

This is not because I am enjoying this process. The people who know me best have seen how five years of relentless persecution, by the industry and government, have worn me down to the bone. On the day before Priya’s plea, as we gathered outside of court, I made an admission that brought audible gasps to some people who overheard what I said.

“I’m done,” I said. “I cannot deal with this. I just want to play with my dog.”

It’s also not because I even feel particularly well-equipped to fight this fight.

“Maybe I’m not supposed to admit this,” I said to the people gathered outside of court “But I’m not meant to be a leader or a public figure.”

I have never felt less confident in my abilities as an activist or organizer. No matter what I try, I feel fundamentally incapable of persuading, much less inspiring, the people around me. And I am tired of people believing that I am a happy warrior. It has felt worse than fake — like an active deception to the people around me.

The truth is this: these last few years have been among the worst of my life. I have been a defendant in four felony criminal cases, and three other civil cases, and those fights have been lonely and overwhelming — against a seeming army of corporate lawyers. Movement infighting, and the disinformation that spreads on social media, have compromised much of the solidarity that makes grassroots movements strong in the face of repression. (That is exactly what disinformation is designed to do.) Virtually all of my personal goals have been compromised, leaving me penniless, professionally-shamed (and perhaps, soon, disbarred), and empty-handed in the pursuit of the goals I set out for myself two decades ago.

And perhaps worst of all, the people who have meant more to me than anyone in the world — the ones who’ve been there for me for my entire life — are gone. My mom. Flash. Natalie. Lisa. And, earlier this year, my little Joan.

“It’s just you and me now, buddy,” I say to Oliver on many mornings. “We’re no longer a pack.”

And yet, even with all of that, the decision to fight this case is an easy one. You’re probably wondering why that’s the case, given all of the above.

The answer is that it’s not my fight. It’s theirs.

When I shared my exhaustion outside of court a few days ago. People gave me encouraging responses: “You can do it. You’ve done it before.”

But here is the thing. I can’t do it. And I haven’t done it before. The unprecedented victories we’ve won in court are not mine.

They are victories won by the animals we represent.

The crucial moment in the Utah trial occurred when I showed the jury footage of Lily, days after she was removed from Smithfield’s farm, hobbling on an injured leg.

The crucial moment in the Foster Farms trial was when we showed video of tiny Jax, debilitated by a virus that had killed so many of his sisters and brothers — but still struggling to stand in a world that should have left him crushed.

And I believe the crucial moment in the Sonoma County trial will not be anything I say, any clever legal argument or rhetorical flourish. The crucial moment will be the power of stories like Qing’s, the bird whose mangled feet left her unable to reach food and water at Sunrise Farms.

I feel tired and defeated and weak.

But I have faith in the power of their stories, and their spirit.

There is a principle in Buddhism, little known, that is called anatta. It is the companion to the more commonly-known principle of ahimsa — nonviolence — but even more important despite its obscurity. And the idea behind anatta is that, if we look at the world only through our own eyes, we are deceiving ourselves. Because, in truth, we are all one.

Our individual view of the world is like a tiny pinhole into the universe. And seeing only through our own individual perspective thus blinds us to important truths.

When I look into the world, and think only of my own struggles and desires, I fail to realize that there is a nearly infinite sea of consciousness just like my own. This universe goes by many names. Scientists like Darwin called it the web of life. Philosophers like Peter Singer have described it as the interchangeability of perspectives. But in all its various descriptions — spiritual, scientific, or philosophical — the central point is this.

We are all connected. And it is when we see and embrace these connections, that we are truly strong.

When I am feeling weak, in the vessel of my own mind and body, I think about the strength that Lily showed us, when she was starving on the floor of the Smithfield factory farm. Her little foot hurt so much, but she kept pushing forward toward food, even when it was never enough. And while she starved for weeks, it is because she kept fighting that she made it out alive.

When I am feeling hopeless, I think of Jax. He was not only too sick to stand, but in a packed slaughterhouse truck, with 5000 other birds crammed up against him, moments from a brutal slaughter. He could have easily given up. Yet he held onto hope, and dragged himself across the cage floor, even as his tiny little legs failed him. And that prevented him from being crushed to death — like so many other birds we found at Foster Farms. And because he had hope, he lives a happy life today.

And when I am feeling despair — when every joy in life seems like it has been taken away — I think of little Qing. She never knew softness or safety, much less happiness, in the dark shadows of the Sunrise Farms cage. And the harsh metal wire, cutting against her feet, would have caused most of us to give up on life.

“What demons have created this world?” I imagine Qing asking herself. “What a cruel joke this life is, where every step is more searing pain?”

And yet Qing still dreamed of a world that would not be harsh metal and pain.

She dreamed of a world that she did not even know existed: a world of sunlight and softness and, yes, of love.

And because she kept dreaming, and did not give up, her dreams came true. This is her, just a few months later, when she escaped Sunrise and found the freedom that every living being on this earth deserves.

So why do I refuse to take a plea?

Because I am not fighting for myself. I’m not even really fighting as myself.

I’m fighting for Qing. And I’m fighting with Qing’s spirit and strength.

It’s her dream — a world where even a little bird, with hobbled feet, is given the care and love she deserves — that inspires me.

And, if a jury is given a chance to see Qing’s dream, I know that it will inspire them, too.

It is that chance – to prove the power of rescue – that compels me to continue on. It’s that fight, that must be fought.

Let the cards fall where they may. I’m going to trial.

In some higher court you've already won, you've been winning all along.

Thanks for speaking truth and being you. I can’t imagine how hard it’s been for you these past few years but I’m glad you exist and our world is better for it.