The sad case of Ruby Montoya

When infighting meets climate activism

When I first heard the story of Ruby Montoya and Jessica Reznicek, it seemed a triumphant one. In July 2017, two women bravely and openly stated that they had drilled holes in the Dakota Access Pipeline, to prevent construction on an environmentally-devastating project that President Trump had re-authorized. It seemed a classic example of nonviolent direct action.

It was wish shock, then, that I read the Economist’s account from early November of how the two women’s relationship — and the campaign they were spearheading — had fallen apart in recrimination. Reznicek now has been sentenced to 8 years in prison, after pleading guilty in the face of charges that could have landed her in prison for life. Montoya, who apparently cooperated with the federal government, is attempting to withdraw her plea and has now stated regret over her role in the actions.

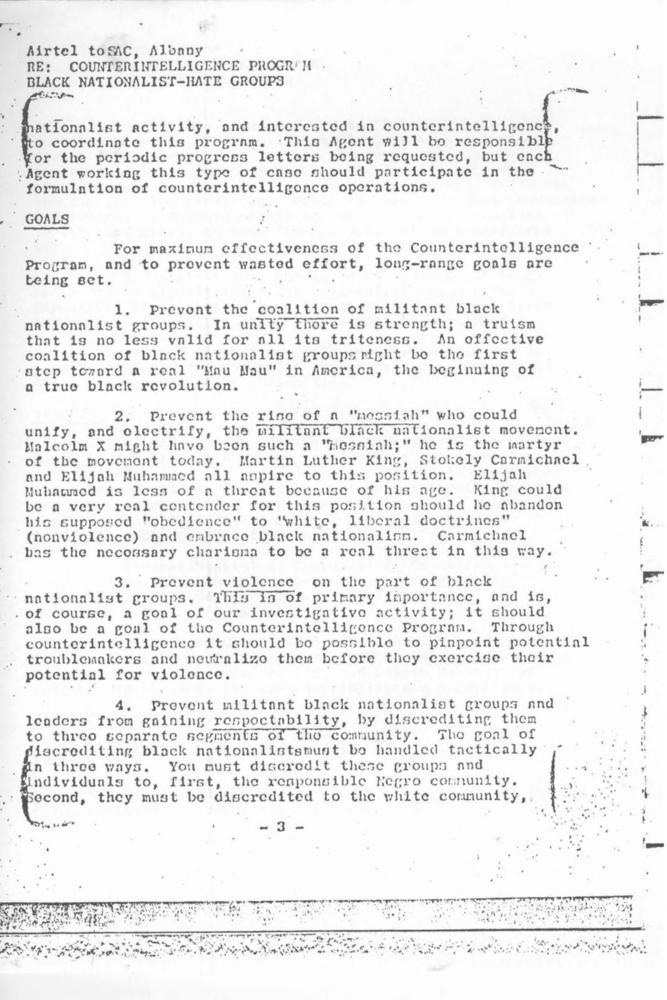

I want to set aside the effectiveness (and ethics) of the action taken by the two in this blog. My focus, as DxE faces prosecutions similar to the ones Montoya and Reznicek faced, is on the breakdown of relationships that appears to have occurred in their case. This is, in fact, common in cases of activist repression. And it’s perhaps partly driven by government tactics. Since the 1960s, the government has used black ops tactics to destroy unity in movements. The famous Counterintelligence Program “COINTELPRO” was launched by J Edgar Hoover to undermine unity in the civil rights movement, and undermine its leadership. Its most famous tactics was the so-called suicide letter — an anonymous letter to Martin Luther King Jr. that threatened to expose an adulterous affair unless King killed himself.

But the sad truth is that government manipulation is often not necessary to divide a movement. And that appears to what happened between Montoya and Reznicek. A failed romance; a series of actions that were not embedded in a supportive community or campaign; and differing risk tolerances between the two women. The result was a combustible mixture that has damaged both women’s lives, and the movement they believed so deeply in. And it never had to come to this.

Some takeaways for me:

Direct action should be a tactic utilized only among people who are prepared for the consequences. It should not be an act of desperation. It should not be taken by people who are not on a solid personal foundation. And it should be grounded in strong pre-existing social relationships unlikely to fray in the face of government repression.

Property destruction is likely to backfire. The damage at issue not only was easily fixed by the pipeline, but led to far more serious criminal charges (and far less sympathy from the public).

Direct action should be grounded in a community. Lone wolf activists are unlikely to survive the strain of repression. The two women not only acted alone, but went on the run after it became apparent that they would be arrested. The strain of that probably contributed to their relationship downfall.

There are many other things one could say. But I’ll just conclude by saying that, despite all of this, the main point for me is still that the government’s actions in this case seem totally out of proportion to the crime. I’ll pray for both Reznicek and Montoya tonight.