The War on Dogs

Millions of our canine friends have been radiated, poisoned, and sent into space. This series will show how we can end the violence.

A quiet war has been raging over the last 75 years. Its victims are typically unnamed and forgotten, though they’ve played a crucial role in a number of historical events: the dropping of the atomic bomb; the first flight into space orbit; and even the inception of modern medical tests. And while the war has been a vicious one, the losses, which number in the millions, have occurred entirely on one side.

The war I am speaking of is the war on dogs. And I face trial on March 18, just over a month from today, because of my efforts to end that war – and bring peace to the animals who love us most. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be writing about how that war began, and how we can bring it to an end.

But to start that journey, we have to tell the story of the dog who was sent to space.

—

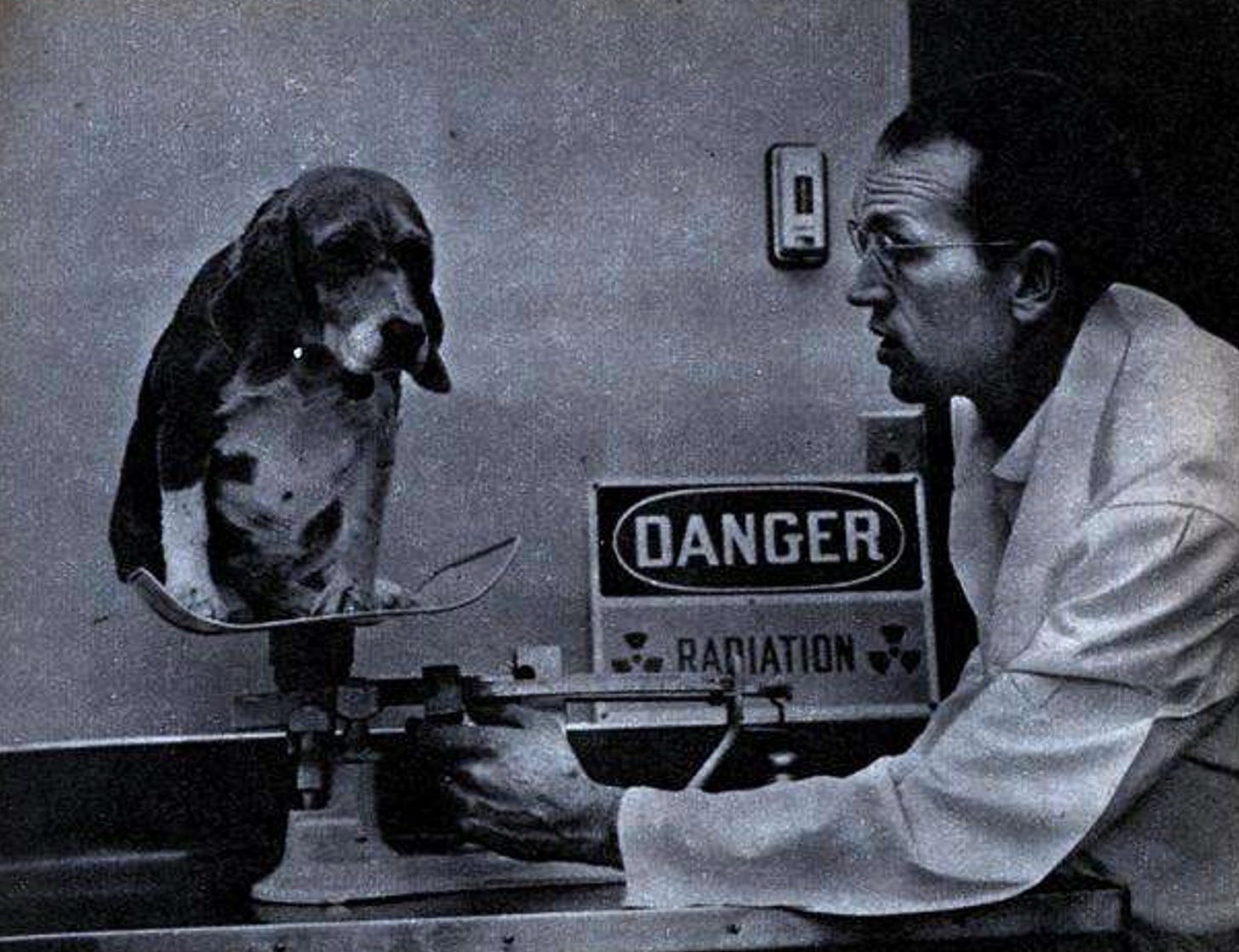

I wrote a few weeks ago about the origins of the beagle as the chosen animal for laboratory experiments. Scientists picked dogs, and the beagle specifically, because they would tolerate years of abuse – including radiation exposure that was 1000 times what was considered safe. But the use of dogs quickly expanded from atomic tests to other experiments.

This includes space flights. Laika was the first animal sent into orbit by scientists in the USSR in 1957. The scientists knew Laika was being shipped to her death; they had no way of bringing her home. They chose a dog because, of all the species, dogs were the most likely to survive in a tiny capsule for endless days. Indeed, they manipulated Laika for many weeks by placing her in smaller and smaller cages, promising her each time that she would not be hurt. But that promise was broken with her last cage, which was rocketed into space. It’s unclear if she died from overheating or suffocation, but we know it was slow and painful. Radio signals from the tiny spaceship show that her heart rate skyrocketed to 240 beats per minute then stayed elevated for many hours before she died in terror and pain.

But perhaps the most important expansion in the use of dogs occurred with toxicology tests. With the massive profusion of chemicals in post World War II society, someone needed to determine whether the substances were safe. Thus, the toxicology testing system was invented, whereby animals would ingest massive amounts of potentially poisonous substances, and scientists would wait to see if they died.

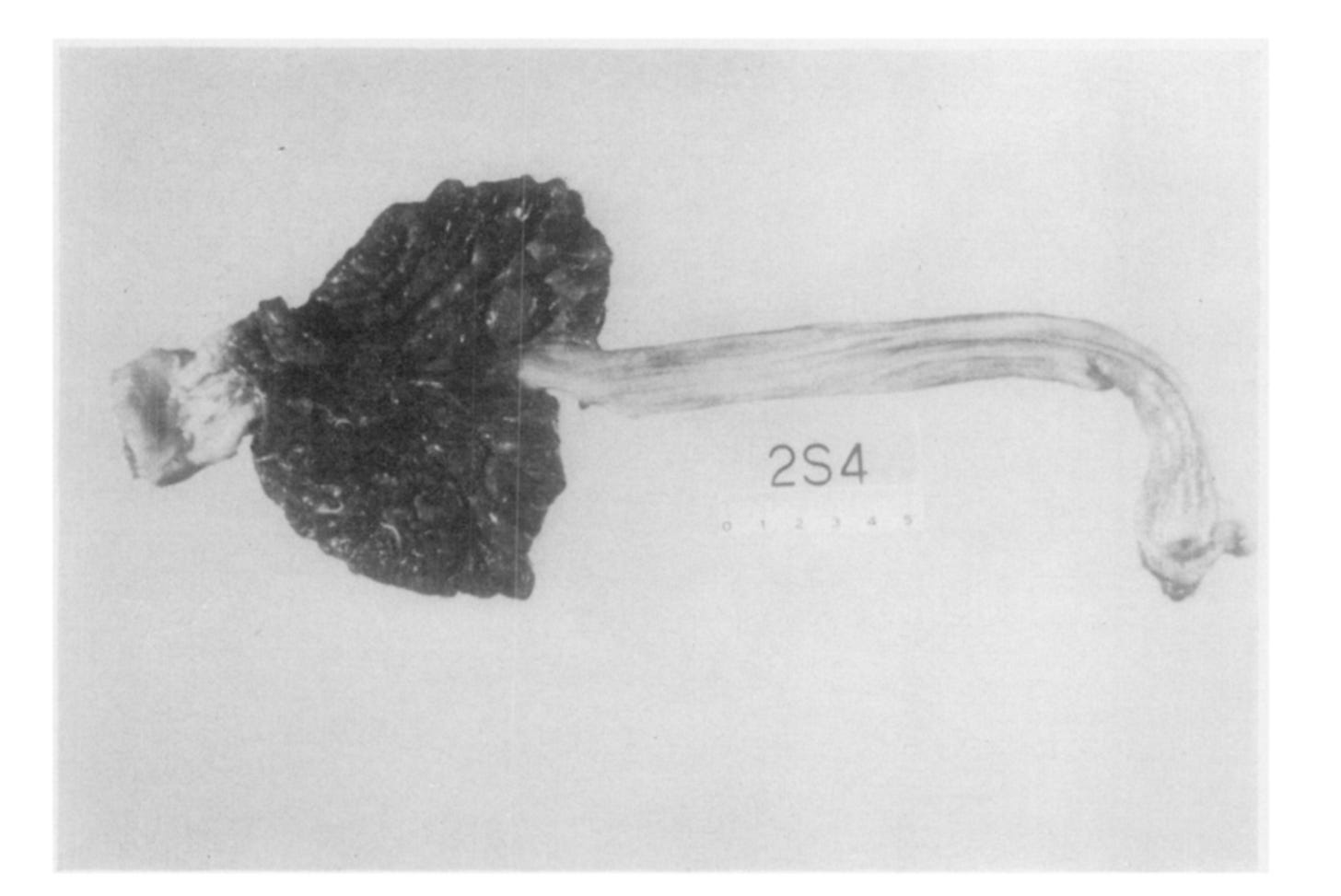

Like radiation tests, toxicology experiments required a victim who was easy to manipulate. Animals would need to be force-fed toxic substances every day, then observed for days, weeks, or even months. Facilities like Ridglan Farms raised thousands of beagles to fill this demand. In 1974, for example, researchers at an institute called the Lovelace Foundation decided they would study the toxicity of industrial chemicals used in laundry detergents. They chose 54 Ridglan beagles for the test. All the dogs were “sacrificed” for study after 6 days. But many lived much shorter periods of time, vomiting blood for hours before they collapsed and died within a single day. The descriptions of the deaths are so grim - “necrotic,” “ulcerated,” “gross lesions” - it’s hard to believe they’re even real.

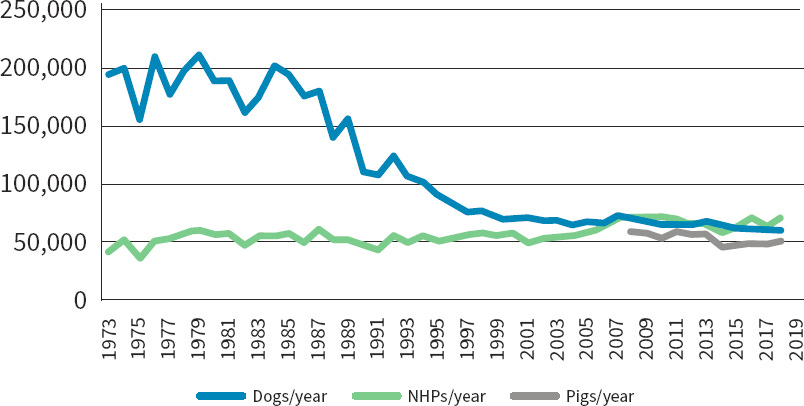

The Lovelace Foundation, however, was only one of hundreds of corporations that began to use dogs in toxicology tests. And at the industry’s height in the 1970s, 200,000+ dogs were used every year in scientific research.

But something changed beginning in the early 1980s. The use of dogs began to dramatically fall, and by the early 2000s, the number dropped to about one third its former size, or around 70,000 per year. While some commentary points to the use of molecular models as an explanation for this decline, that doesn’t quite explain the change. The total use of animals increased over much of that same time period, despite the rise of molecular models. It was only dogs, cats, and other charismatic animals who saw their numbers drop.

Something else important happened in the 1980s: the birth of animal rights. In 1981, PETA executed the first undercover investigation of a vivisection facility in American history in Silver Springs, Maryland. Monkeys were found with fingerless hands, exposed to the bone, after their nerves had been severed in gruesome surgical experiments. While the authorities initially seized the poor creatures as victims of cruelty, a judge ordered them returned. The monkeys miraculous disappeared before the judge’s order was enforced. It was the first ALF liberation in US history. (That story is told in Ingrid Newkirk’s groundbreaking book Free The Animals – a must read.)

For the first time in history the abuse of animals in labs became a subject of public dispute. And when the public was shown the truth, the public did not like what it was seeing. For the next 20 years, vivisection – especially of charismatic species like dogs – was on the defense.

Then something changed again and halted progress around the year 2000. For years after the Silver Springs case, the greatest fear of vivisectors was legal exposure. A criminal prosecution would not just threaten the individual vivisector; it posed a threat to the existence of the corporation that was sponsoring the experiments. But after years of animal rights exposés, the biomedical industry found a solution. Instead of defending themselves from legal action, they could just take over the government. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which was charged with enforcing the Animal Welfare Act, became a revolving door for industry beginning in the early 2000s. The appointed leader of the USDA for decades was someone who took a consumer perspective on the department’s mission. But, beginning in 2005, the USDA has been controlled by corporate interests under both Republican and Democratic administrations. And animals, including dogs, have paid the price.

For example, the USDA’s own internal watchdog noted in 2005 that enforcement actions against animal abusers had become “basically meaningless.” Vivisectors were treating animal abuse allegations as a cost of business, and not a very expensive one, at that. This continued through the next decade, with reports by the internal watchdog in 2010 and 2014 making the same finding: the government was asleep at the wheel. It is no surprise that, over this same time period, the numbers of animals used in research, including dogs, ended their decline, despite increasing public opposition to the use of animals in medical tests. From a high of over 2 million (excluding birds and rodents), the total number of animals used in research dropped to around 700,000 by the 2000s and has not budged since. The use of dogs, in particular, plateaued in the early 2000s at around 60,000.

This is not because the industry has ended the torture of dogs. While vivisectors have become smarter about disclosing the details of their experiments, there are still shockingly gruesome details published in public scientific journals. For example, in 2016, 36 Ridglan beagles were used for toxicology testing of a new artificial sweetener called monatin. The male dogs saw their testicles shrink, and all the pups were “exsanguinated” – i.e., drained of their blood – so their bodies could be vivisected. In 2014, 12 beagles were filled up with fluid, like balloons, until their leg muscles blew up and bled. They were observed for 2 weeks, then vivisected; scientists found that their muscles were necrotic - dead and rotting - as a result of the experiment.

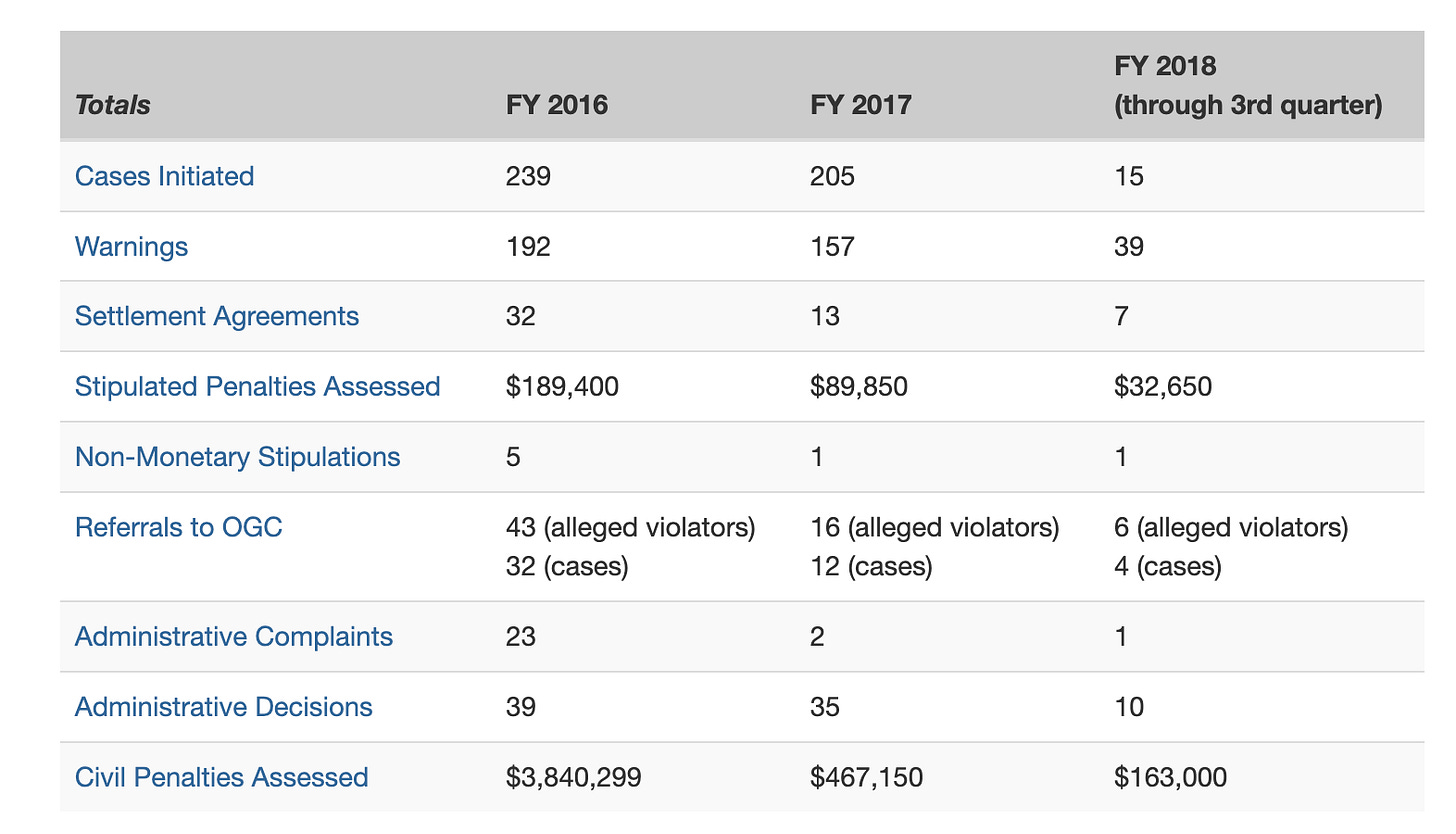

In short, the abuse continues; the difference is that the industry has much less concern that abuse will lead to consequences. Perhaps the most important reason for this is that the government has not only declined to enforce the law. It has actively conspired with the industry to cover up misdeeds. In 2006, the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act passed, threatening activists with federal charges for otherwise nonviolent acts. One of the new law’s first uses was the prosecution of activists as terrorists for chalking against vivisection on public sidewalks. In the early 2010s, “ag gag” laws spread across the nation, criminalizing the act of taking a photograph in a factory farm or a lab. But in 2017, the industry offered its master stroke: it made all the animal welfare inspection records disappear by convincing the USDA to shut down its public records database.

It should come as no surprise that, within one year of that records purge, the enforcement of federal animal cruelty law fell off a cliff. Administrative complaints – the primary mechanism for enforcement – dropped from 23 in 2016, to 2 in 2017, and only 1 in 2018. Warnings went from 192 to 157 to 39. And perhaps most disturbingly, civil penalties dropped from $3.8 million to $0.47 million to $0.16 million. For an industry that receives $15 billion a year in government subsidies, that $0.16 million was less than a drop in the bucket.

The events of 2016-2017 demonstrated the industry’s immense political power. You may have convinced one government official, on one occasion, to enforce the laws protecting animals from abuse. But over the long term, the industry showed, we control the levers of power.

The war on dogs, which had been challenged so successfully by exposure and accountability, was starting again. And the government was firmly on the side of those who were killing dogs.

And that’s where we stepped in. As enforcement was plummeting, and abuse surging, I and a number of other activists decided we needed to take direct action. So we stepped into Ridglan Farms; what we found has the potential, at our upcoming trial, to permanently end the war on dogs.

I’ll tell the next stages of that story in the coming weeks. But in the meantime, please help us get ready for that trial.

We have such a horrible history of violence towards animals. Thanks for what you do, Wayne.

Our species is a demon to the animals, but you're an angel, Wayne. . .