Why Do We Torture The Ones Who Love Us Most?

Political narcissism is threatening everything. To cure it, we need a culture of care.

I was born to an immigrant family in a county that was 80% Republican, 98% white, and 100% hostile towards anyone who was different. Kids made fun of my accent and laughed when I fell and broke my glasses in the first grade. They laughed even harder when I came to school the next day with a mess of tape and plastic on my face.

But there was one kid who, despite my low social status, always loved me. He would ask me to play, even though I would make us both look bad when I inevitably tripped chasing a ball. I brought him strange-looking bugs or purple-colored rocks – not exactly the most popular hobbies in the grunge-rock era of the 1980s and 90s – and he was into it.

To this kid, and only this kid, I was cool.

Oh, I forgot to mention: This “kid” was a dog. A beagle, specifically. My neighbors had a brown puppy who ran around like a furry tornado in their front yard. And I decided shortly after meeting him that he was my best friend.1

“If those mean kids ever come for you,” I said. “I’ll stick up for you. Don’t worry!”

He barked and nodded and didn’t seem worried at all.

I’m not the only kid who wanted a beagle. Beagles are cherished because they are among the most loving of dogs. The American Kennel Club notes that beagles are “happy go lucky,” “friendly,” and “funny” and gives them the highest possible rating with children (5 out of 5). A human, including a rambunctious kid, can poke and prod a beagle endlessly, and she’ll still be happy for more.

That unconditional love was exactly what I needed growing up. When the world felt scary, I had a beagle to keep me safe. My neighbor’s beagle opened me to new experiences – friendship, trust, and unbridled joy – that were otherwise missing in my life. I have loved dogs more than anything ever since.

It was thus a shock when, a decade after I met my first beagle, I read Animal Liberation and learned that the exact breed who loves us most is also the breed we torture in labs. And it is precisely because they love us so much that they have been chosen for this vile sacrifice.

Betraying man’s best friend

We consider ourselves a nation of dog lovers. Very few crimes are more hated than crimes against pups. The former NFL star Michael Vick went from being one of the most adored people on the planet to one of the most hated when the public discovered he brutally killed a few dogs. And yet unbeknownst to most Americans, thousands of beagles go through experiences far worse than Vick’s dogs in laboratories every year. And the villains in that story are not just getting away with criminal abuse; they are funded by the federal government.

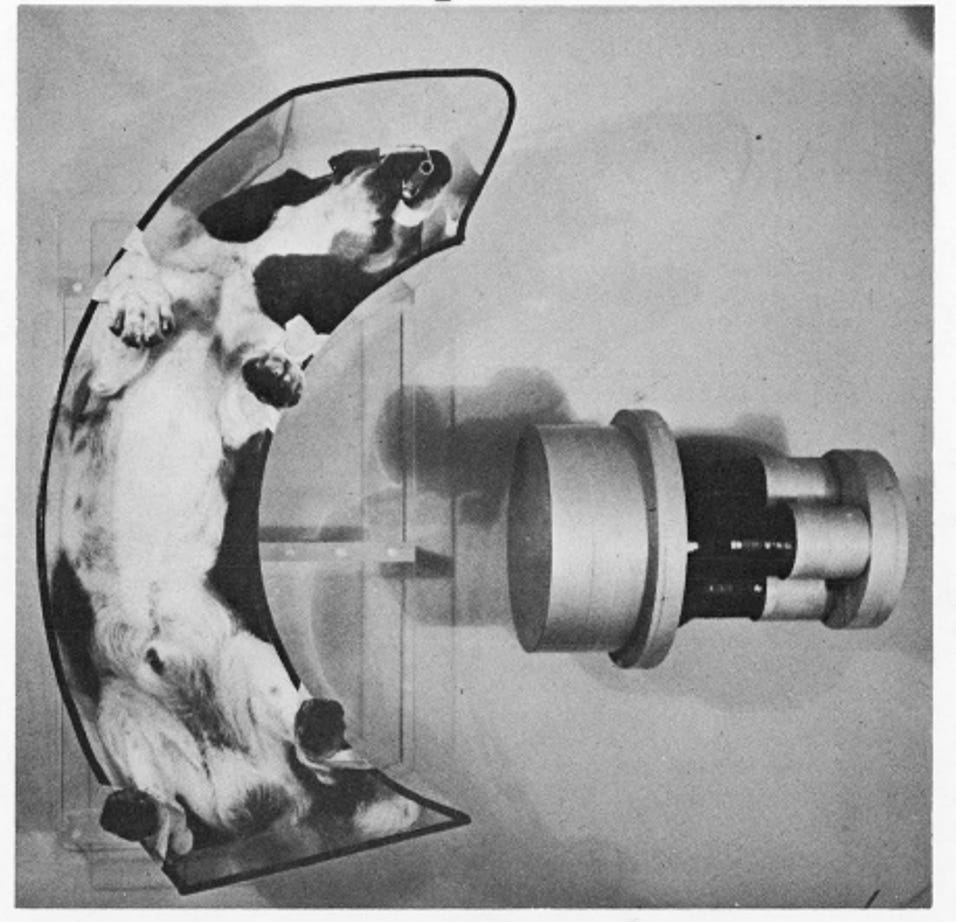

Beagles were first chosen as experimental subjects at the height of the Cold War in the 1950s.2 After the United States dropped two atom bombs on Japan, it occurred to the government that someone should start looking into how radiation might affect living beings. While scientists initially planned to use monkeys for these experiments – in which animals would be subjected to radiation levels 1,000+ times what was considered safe – it was ultimately decided that it would be too hard to breed and control the hundreds of monkeys necessary for the tests. These new experiments would require a species that was fine with being poked and prodded as lethal doses of radiation slowly burned away their bodies over weeks, months, or years.3 There was only one species that trusted us so much that it would tolerate this extended torment: the dog. And beagles, because of their loving nature, were the perfect test subjects.

While very little was apparently learned from these radiation experiments, a profitable industry was spawned. Suddenly, the federal government was in the market for thousands of laboratory dogs. And in the decades since those early experiments, beagles have been chosen for all manner of horrifying experiments, from grisly facial disfigurement surgeries to force-feeding of laundry detergent. In modern America, around 60,000 are used in experiments every year. What ties all these cases together is that the experiments require a subject who will tolerate abuse. That only happens when the experimental subjects are blessed (or cursed) with unconditional love.

From beagles to politics

Our violent relationship with beagles, however, is not the only example of this very unique form of betrayal. Consider our most painful personal relationships. “The ones we love are the ones who hurt us most.” It’s been said so many times that it’s now a cliche. But it has certainly been true in my personal life. Though I have been smeared, physically beaten, and even imprisoned by powerful adversaries, the blows that have hurt most are those inflicted by those I loved. Nearly a decade after it happened, I’m still scarred by the accusations of one of the key leaders of DxE, a dear friend who became convinced (falsely) that I was conspiring to oust him from the organization.

But there’s a political analogue to this personal betrayal that was identified by Sigmund Freud in 1917: the narcissism of small differences, or what I’ll call “political narcissism.” Freud’s point was simple: the people who are ideologically closest to us are the ones we fight most viciously with. We see political narcissism when activists battle over racial micro-aggressions (“How dare you ask me where I’m from!”) and abstract language disputes (“It’s not Latino! It’s Latinx!”) while they ignore powerful people who are literally getting away with slavery and murder. Like the vivisectors with the beagles, we attack our allies precisely because they love us most. Our allies are easy to manipulate and won’t fight back. That allows us to impose our will on them – even when it comes at great suffering and social cost.

Political narcissism has become a dominant form of discourse on the left, especially of those under the age of 30. Virtually every debate focuses on my feelings rather than social impact. The inevitable result is that the hard work of organizing – debating and reaching consensus, despite individual differences in feelings – never happens. Worse yet, people — even university presidents — are scared to say what they actually think, even when their perspectives are desperately needed. Caring people are afraid of being accused of hurting someone precisely because they care.

A friend recently shared with me his experience working in a pro-Palestinian activist group. When he brought up with the group that he thought they should be willing to condemn the violence of Hamas, he was disinvited from a future event. His alleged crime? He had made another activist, who was Arab, feel unsafe. My friend is super low key and humble, and there was no discussion of whether his suggestion was right or wrong for the movement, or simply framed in the wrong way. Instead, the discussion began and ended with another activist’s individual feelings. The lesson from this experience? Don’t say what you think because, if someone disagrees, they’ll attack or oust you. Many people, including perhaps my friend, will simply choose to not participate at all. Like beagles, they will not fight back precisely because they love the very people who are coming for their head.

From politics to beagles

Political narcissism threatens everything. Before you accuse me of exaggeration, note that human beings are only able to achieve anything, including our survival, because of our ability to cooperate. That is the one and arguably only thing we do well. And as political narcissism ascends, cooperation deteriorates. If even allies can’t sit at the same table together, our species is doomed.

But there is a very simple solution to the problem that we can learn from our beagle friends: a culture of care. The problem with political narcissism, after all, is not that allies feel love and care for one another. That is a good thing. The problem is that this love and care is weaponized by political narcissists in a way that destroys our ability to cooperate.

Let me clear that this is a cultural, and not personal, problem. All of us behave like political narcissists at times, if only because our view of the world is distorted by our own feelings and experience. We need others to check us when this distortion is undermining our ability to act with care. That collective effort can take the form of a very simple test:

Are the actions I am seeing showing care, especially when things are tense? If not, I should intervene.

If someone had intervened when my friend was so quickly condemned in a pro-Palestinian activist group, perhaps he would still be involved – and the movement to support victims in Gaza would be stronger. For example:

I love you all like brothers. I wonder if there’s a way for us to show disagreement with his position while also showing him lots of love and respect for being here? I know he loves us. He wouldn’t be here otherwise.

If someone had intervened when the first beagle was placed in a cage, tens of thousands of lives could have been saved. For example:

I know we’re scared by all this stuff about radiation. But so are these dogs. Is there a way for us to address that fear without torturing the ones who love us most?

Those interventions didn’t happen. It is not, however, too late. Every day is a new chance for us to fight for a culture of care, one where we no longer target those who love us most. But we have to be willing to fight for it.

And in my next newsletter, I’ll share how I and my two co-defendants, Eva Hamer and Paul Picklesimer, are risking our freedom in that fight.

—

Some notes for the week

The legendary gay rights activist and lawyer Evan Wolfson is joining Open Rescue Advocates for a conversation this Sunday at 10 am PT. Come in person if you can, as we’ll only be taking questions from the crowd in San Francisco (but others can observe remotely). Evan is arguably the most successful legal activist of our generation. Here are the event details.

After the event with Evan, I’ll be having an informal lunch from 11:30 am - 12:30 pm with folks who have thoughts on my recent blogs that have referenced the conflict in Gaza. I’ve had many good friends reach out on various sides of the debate, and I’m hoping an in person conversation can be a good opportunity for us to practice building a culture of care, and educating ourselves about aspects of the conflict. We’ll grab Mr Charlie’s across the street.

We’re also hosting a legal “hackathon” — i.e., an informal brainstorming and work session — at 1 pm on Sunday at our offices in San Francisco. This will be invite only, but if you’re interested in helping out with the legal work on the upcoming Ridglan trial, I encourage you to join. Snacks will be provided! Email us at info@simpleheart.org if you’re interested.

I don’t recall the dog’s name or gender. But I am using “he” for narrative convenience.

Most of what I know about beagle experiments I learned from my friend Jeremy Beckham, who has done some of the most important work on animal experiments in animal rights history. If you are interested, I can share more resources and citations, based on Jeremy’s groundbreaking work.

The dogs’ bones became so brittle from radiation that many had dozens of fractures by the time they died.

Unfortunately, not just the poor beagles but especially farmed animals who have been selected and bred to be gentle, child-like, peaceful creatures who do not fight back. 😢😢

So hard to read, even though I knew this already. I have a beagle, and this hurts. I’ll do anything I can to share this article with others. It’s so true that “ the truth hurts.”