Every Ten Years, Open Rescue Has Reshaped Animal Rights

A wave of animal rescues has driven progress for animal rights every decade. What will the next wave achieve?

What’s up this week

As if on a timer, open rescues have changed the face of animal rights every 10 years. I break down how that happened, and predict what change this decade will bring, in this week’s newsletter.

The federal government is making massive purchases of pork to prop up an industry that’s dying. The pig farming industry has suffered “the worst five months of average losses in 20 years.” But instead of encouraging transition to more ethical and sustainable foods, the US government is spending tens of millions to buy pork that no one else will buy.

The date has been set for my trial in Sonoma County, where we rescued dozens of sick and injured animals in 2018. In September of that year, dozens of activists were arrested and charged with felonies for giving aid to collapsed and starving animals at the largest organic poultry farm in the nation, Perdue Farms. Now, almost exactly 5 years later, we will be going to trial, beginning on September 8. Here’s more about the case.

I spoke this past Sunday at the Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco on the growing evidence that factory farming poses an existential environmental threat to the planet. That includes drying up the Colorado River, which provides water to 40 million Americans. You can watch the lecture here:

What’s up this week

I have always thought that open rescue is the canonical act of animal rights. But even I did not realize, until recently, the historic importance of rescues in driving progress over the last half century. Indeed, every ten years, as if on a clock, a wave of rescues spurs massive changes in public consciousness and movement power for animals. And if activists meet the challenge today, we will soon be in the fifth wave of open rescue in animal rights history — and this wave presents opportunities to change not just awareness but the underlying systems of abuse.

But to understand why, we have to start with the beginning.

The First Wave: The beginnings of a movement (1980s)

In 1981, there was hardly an animal rights movement to speak of. The legendary philosopher Peter Singer, who penned the groundbreaking book Animal Liberation in 1975, was still a young scholar without much of a following. While organizations had existed to protect dogs and cats for over 100 years, protection for most animals was grounded in “nuisance” laws; these laws made it unlawful to brutalize animals only when the cruelty was deemed a public nuisance to the surrounding community.

“Out of sight, out of mind.”

The result was, as the violence was hidden away in labs and factory farms, and grew exponentially in both severity and scale, there was virtually no organized opposition.

Until open rescue.

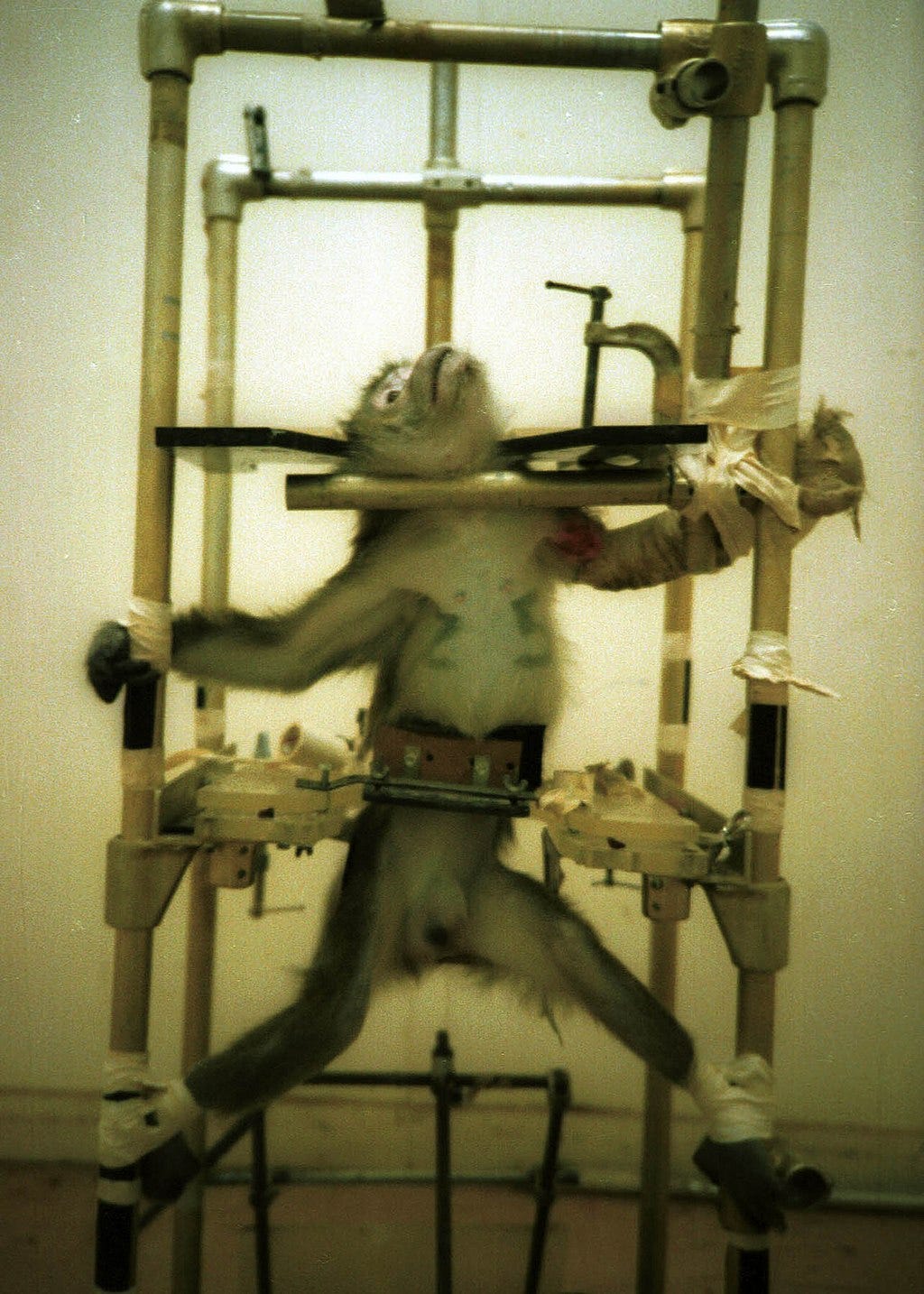

“Open rescue” was not what it was called, at the time. There was no language, much less strategy, behind the idea of openly defying the authorities to give aid to suffering creatures. But then activists in Maryland discovered that monkeys who had been gruesomely abused in a laboratory — some suffered so much torment that they were literally chewing their own limbs off — were going to be returned to the scientist who had tortured them. They decided to take direct action. They went to the building where the animals were being held, and without asking for consent, simply rescued them. (You can read the rest of that breathtaking story in Ingrid Newkirk’s book, Free the Animals.)

The nationwide media coverage that resulted from the dramatic rescue rocketed a new animal rights group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, into the public consciousness. Animal rights, for the first time in history, was a movement.

The Second Wave: The shift to farm animals (1990s)

For most of the first decade of animal rights, however, the animals who are most commonly tortured by human beings — farm animals — were almost entirely ignored. A 1990 study, for example, showed that attendees of the major animal rights conference at the time believed overwhelmingly that the use of animals in research was the movement’s highest priority. Only 18% of the activists at the conference were themselves vegetarian.

Then, in 1993, open rescue changed everything. In that year, a young and courageous Australian activist named Patty Mark was tipped off about the abuse of hens in a local egg farm. When the authorities refused to act, Patty took it upon herself to enter the farm to document what was happening — and give aid to the animals. She named her actions “open rescues.” And those early open rescues by Patty and her group Animal Liberation Victoria triggered international attention and put farm animals front and center in animal rights.1 Within a decade, the percentage of vegetarians within the animal rights movement had doubled, and farm animals became the #1 concern.

The Third Wave: The power of grassroots direct action (2000s)

But even as the movement’s focus shifted to farm animals, its power remained limited. While organizations such as Vegan Outreach spread the vegan gospel one person at a time, per capita meat consumption continued to rise. The animal rights movement did not have a strategy for challenging the power, wealth, and sheer inertial force of animal exploitation.

Then open rescue triggered another evolution in animal rights, one decade after Patty’s pioneering work in Australia. Karen Davis and United Poultry Concerns brought Patty to speak at a conference in 1999, and a number of US groups were so inspired that they began to experiment with taking a similar approach. Grassroots groups across the country, from Utah to Minnesota to New York, began mobilizing in teams to give direct aid to animals. And, by 2003, the movement for open rescue had gone viral, with the most notable open rescue group, Compassion Over Killing (COK), triggering impressive coverage and dialogue in The Washington Post.

This wave of rescue was not just a new way to expose abuse, however. It demonstrated a new way to build real political power. By inspiring people across the nation to get active, open rescue was fueling a new approach to social change, one focused on building large networks of ordinary people to fight.

The Fourth Wave: Fighting the humane lie (2010s)

But there were two major obstacles to the continued growth of this new grassroots movement. First, legal repression threatened to cut the movement down. Leadership in these new grassroots networks was targeted, on the theory that you could cut the head off the snake. Second, the industry was doing a wonderful job of convincing the public that its historic problems had been overcome. The open rescues of the 2000s exposed horrific abuse. Industry reforms in the 2010s convinced millions of Americans that the problem had been solved by humane meat.

Then open rescue changed the movement again. Beginning in 2013, almost exactly one decade after COK reached national media with its open rescues, I and a few friends started a grassroots network, Direct Action Everywhere, with one ultimate goal: rescue the animals, no matter what it takes. And our particular focus was to identify the very facilities that the last wave of animal rights activism had hoped to create: the mythological “humane” animal farms.

What we found was, in Michael Pollan’s words, a black eye for organic agriculture.

The result of our Whole Food exposé was a grassroots mobilization that was unprecedented in scope and size. This was not a movement just to protect dogs and cats, or even primates and chimps. And it was not a movement that could be easily sapped by industry propaganda. The animal rights movement, which for most of the last 10 years had been working hand in hand with industry, would never be the same. The goal of “animal welfare” was quickly being replaced by “animal rights.”

The Fifth Wave: Changing the system (2020s)

Even with dozens of open rescues happening across the country, however, it seemed extraordinarily difficult to create long term change. While the animal rights movement witnessed bursts of media coverage, viral social media videos, and nonviolent occupations at some of the largest factory farms in the nation, something was still missing: We weren’t changing the system in a material way.

Then open rescue, once again, cleared the path. The recent trials in Beaver County, Utah and in Merced County, California — both heavily agricultural counties — ended with historic and unanimous verdicts in favor of animal rights. Indeed, the power of open rescue to sway even a conservative jury is the only reason I am a free man, and able to write this blog post today!

The difference, with this last wave of rescue, is that we are not content with mobilizing support for rescue within the movement. We are normalizing the idea of rescue with the entire world.

But there is one major problem: while the strategy of normalizing rescue to change the system has been working beautifully, very few people are adopting it! This is partly due to COVID-19, as our society became accustomed, due to the pandemic, with a certain lethargy. But the biggest reason for this limitation is simply that we haven’t tried. DxE, the organization I co-founded to push open rescue, has taken on a huge number of projects far beyond rescue. While many of these are great projects — protests, ballot initiatives, etc. — it has left a gaping hole in the movement.

Who is building the movement for rescue? The answer, quite simply, must be each of us. And that is why we created The Simple Heart last year: to empower you to become part of the movement for rescue.

There’s a lot more strategizing and organizing to be done around rescue. I have yet to complete the design of the Open Rescue Experience that I plan to deploy at the Animal Liberation Conference in a few days! But what I do know is this: if there’s no one imagining the future of rescue, we won’t be able to harness its power.

But if you and I choose to engage in that vision-setting process — and imagine a world where not tens but tens of thousands of animals are rescued from hell — we can fulfill the open rescue movement’s greatest dream. We will make liberation, and not torture, a reality.

I hope I’ll see you at the Animal Liberation Conference for the Open Rescue Experience on June 11!

Even before Patty Mark, Gene Baur at Farm Sanctuary had begun rescuing animals from stockyards in Pennsylvania. But unlike Patty’s rescues, Gene’s rescues did not spawn a movement — until much later. (NOTE: Karen Dawn, a writer who has published animal rights pieces in some of the biggest publications in the nation, notes that I neglected to mention the role of Lorri in that first rescue with Farm Sanctuary. Here is Karen’s full note, which should be read:

So beautiful to see Patty Mark getting the credit she deserves, then a little painful to read: "Even before Patty Mark, Gene Baur at Farm Sanctuary had begun rescuing animals from stockyards in Pennsylvania. But unlike Patty’s rescues, Gene’s rescues did not spawn a movement — until much later. " To the best of my knowledge (though Gene can correct me if I am wrong) Gene did not do a single rescue in those days without the extraordinary Lorri Houston, who later became Lorri Bauston, when she and Gene married (as he was Gene Bauston), and Lorri was certainly a fundamental part of that first rescue of the ewe named Hilda. For twenty years their work together building Farm Sanctuary was extraordinary. Then they divorced, Lorri was kicked off the Finger Lakes farm, and not even allowed to see her beloved animals. She started again, and formed Animal Acres in Los Angeles, a brilliant media move, and when things went sour there (Lorri's skills at the time were glorious communication on behalf of animals rather than managing employees) Gene and Farm Sanctuary took that too. Lorri, bless her, then helped run the Thich Nhat Hahn center in San Diego.

Gene is a magnificent activist, as is Lorri. It's time to un-erase her name from the founding of Farm Sanctuary given that she gave it twenty years of her life.

Wayne, I know you are sensitive to the disposability of women in our movement. Lorri, co-founder of Farm Sanctuary, and very much part of the first Hilda rescue, is a prime example.

I just tried to find video of the amazing gal, and it was hard. They really have erased her. But I remembered her gorgeous introduction of my speech at AR2009. Watch the first 90 seconds of this and see the grace, beauty, vivacity and strength our movement lost when it disposed of Lorri:

Thank you, I will look forward to reading this….sadly I can’t do too much as I live in England.

Your legal studies must have helped as you knew what is and is not within the law…

You always have the right words at the right time! 💕