What the stunning Republican victory in Virginia tells us about race politics

A circular firing squad is destroying the American left

My first activism, over 20 years ago, was a campaign to end capital punishment in Illinois, which disproportionately affects people of color. My first community organizing occurred in the projects of the Chicago Southside, where I served Black families and kids in a program called “Read to Me.” And my personal life experience has been shaped by racial discrimination. My dad was told “There’s no place in this country for a man from China,” after he arrived here as a student in the early 1970s, shortly after the Immigration and Nationality Act finally removed racial quotas that barred Chinese people from coming to this country for nearly 100 years. When I was growing up, kids regularly made fun of me, as the sole person of color in my school in central Indiana. One of the most painful jokes told was, “Is your cum yellow, too?”

Partly due to these racial dynamics, I had barely a friend for 2 decades, beyond my dog and a tiny Chinese community. Race, whether I wanted it to be or not, was always on my mind.

I am, in other words, not just a natural supporter of the movement for racial justice that has exploded nationwide since the murder of George Floyd. I am a beneficiary of the movement, as is the entire AAPI community, and I have written extensively about racial issues within animal rights.

So it might surprise you, that over the last 10 years, many leftist activists have accused me of having sympathy for white supremacy. And I think the story of how it all started provides some insight into how modern leftist race politics has gone astray, culminating in the election of seemingly fringe right wing figures like Glenn Youngkin and Donald Trump.

—

In early 2016, a white activist shared on his personal page a comparison between animal rights activists and civil rights activists. I don’t remember the exact image, but on one side, Black anti-segregation activists were sitting in at lunch counter; on the other side, animal rights activists were engaged in an occupation of a similar retail location being protested for animal abuse. The text with the image was something to the effect of, “Disruption works.”

The comparison was a bad one for two reasons. First, comparing animal rights activists who faced minor condemnation for acts of disruption to civil rights activists who were sometimes murdered was perceived as arrogant and self-aggrandizing, regardless of the intentions. Second, many Black folks have objected to the constant usage of analogies to King and Civil Rights to promote other movements. (It’s an inverse version of Godwin’s Law: if you talk about a social justice issue long enough, someone will invoke Martin Luther King, Jr., often without reading any of his actual work.)

But even if the post was a bad one, it was not an offense that required, in my opinion, condemnation of the person, much less disassociating him from the cause. It would not just be unethical to do so, given that the person’s actions were unintended, but strategically disastrous. My family’s other experience with persecution — the tyrannical Red Guards from the Cultural revolution — taught me that. When a movement moves from a politics of liberation to a politics of punishment, it doesn’t just lose its focus; it loses the moral foundation on which it must be built.

Nonetheless, two Black activists within the DxE network pushed for punishment. I had a long call with them. I listened to their concerns, and stated that I agreed with them. I apologized repeatedly for failures to do more to include Black activists. And I discussed with them ways we could include more Black people within our community, including offering financial stipends (at a time when DxE had very little funds, and they came almost entirely from me) to BIPOC activists and sharing more content from pages run by Black vegans. (We ultimately did both of those things.)

But I continued to oppose one aspect of their proposed solution: punishing the white activist. DxE was founded on an “open model” and was firmly opposed to the culture of calling out. The evidence from social movements showed that purity politics was a threat that would undermine our ability to create change. And while I mistake had been made, I did not see it as a capital one. This was a well-intended post that had a negative impact. And I think it was important that we show our movement was forgiving one, and one open to disagreement.

I explained to them that, on a personal level, I was a victim of racist violence but had forgiven the perpetrator.

“I have had my face sliced open by white supremacists calling me an ‘ugly ch***.’ I was sent to the ER to have my face stitched back together and I still have scars on my face – to this day,” I wrote. “And you know what? I still love the people who did this to me.”

I did not condemn anyone for having a different reaction. I simply wanted to explain mine – and the philosophy upon which we had founded DxE.

Then things got on the internet.1 And this nuanced difference of opinion was later transformed into a simple factual assertion that “DxE is not a safe space for black people” (by a prominent white activist) and that we had created an “on and offline environment that alienates oppressed groups and emboldens racists to create dangerous spaces” (by a white journalist for a fringe leftish publication). People began widely condemning DxE for being non-intersectional and sympathetic to white supremacists. And, motivated by fear as much as racial justice, two chapters of DxE closed down, including what was then our most prominent chapter in Vancouver. It was a circular firing squad on the internet.

I don’t want to exaggerate the real world impacts. In the Bay Area, where most of our activists knew each other in person, and which formed the core of our grassroots organizing, the internet arguments barely had an impact. And, despite the online attacks and the collapse of two chapters, our organizing over the next year only became stronger. This is consistent with the evidence from social movements. Maintaining an inclusive culture, in the face of pressures to close ranks, is crucial to movement growth. As the political scientist Hahrie Han points out, research shows that effective movements “engage people who do not necessarily agree in association with one another.” But decisions like the one I made, 5 years ago, are becoming increasingly rare.

And I can’t blame people. As bad as things were for us, 5 years ago, the attacks on us for fostering white supremacy never reached the mainstream media. (Other false attacks, sadly, eventually did.) And the culture of retribution within grassroots movements has only grown. It often seems there’s no room left for kindness. But the inability of leaders to grapple with these issues — and make the difficult decisions that will allow us to build broader coalitions — is now showing up in national politics.

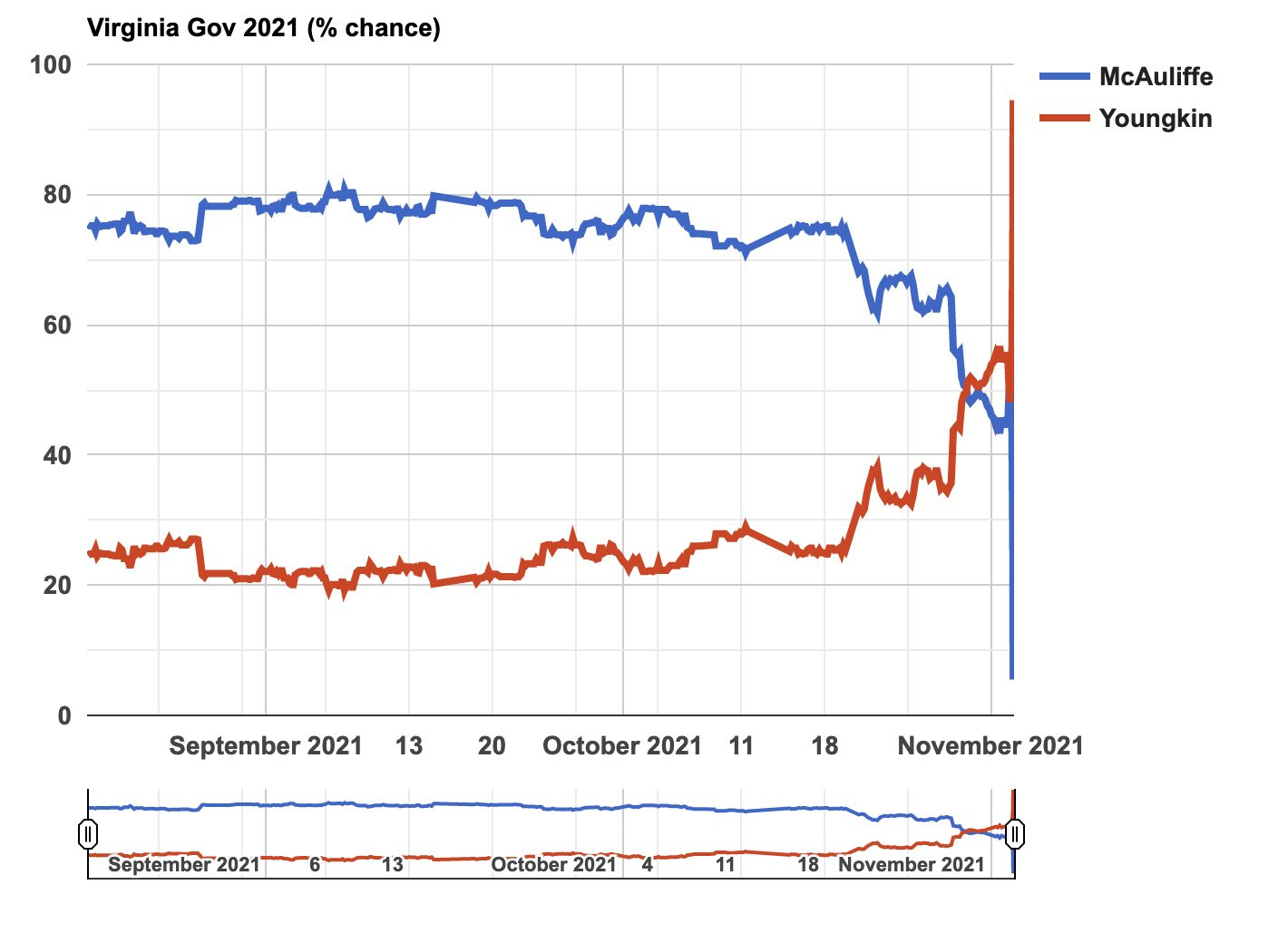

It’s hard not to see Donald Trump’s election as partly a result of a failed politics on race. And now Glenn Youngkin’s win in Virginia, which narrowly focused on the issue of critical race theory in Virginia schools, demonstrates that, even in Blue states, people are rejecting the politics of punishment on race. Many people now wrongly believe that racial justice is more about punishing microaggressions than saving the lives of people like George Floyd.

To be clear, the politicians who are spreading these narratives are probably not acting in good faith; they are using the tool of race politics to secure power. But the opening provided to politicians such as Youngkin and Trump is a self inflicted wound.

Our nation can’t make progress on race when the mere act of sharing a different perspective, based on a violent encounter with racism, is a sign of racial betrayal.

There are a lot of other complications that I’m glossing over, including the overreaction of certain white activists to threats that they would be punished that were never very credible. (In this regard, Robin DiAngelo’s book White Fragility does have some genuine insight.) And I don’t mean to absolve myself of mistakes in discussing these issues. I’m quite confident that some of the things I said or posted were insufficiently empathetic. But the general thrust of the debate was whether my personal compassion for those who had assaulted me was a sign of sympathy for white supremacy. That is a demonstration of how far we’ve gone with the politics of punishment.

great post Wayne