Religion is dying. Is that killing us, too? (Podcast)

Organized religion began to collapse in 2000, just as another behavior skyrocketed: Suicide.

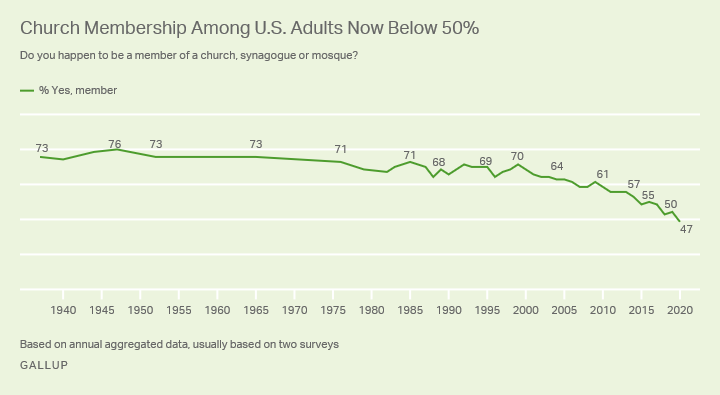

One of the most striking features of modern American life is the decline in organized religion. A country that was founded in part on religious fervor was, for the first time in its recorded history, comprised mostly of church non-participants in 2021, when Gallup measured church membership at a mere 47% of the population. This historical moment, from religious to non-religious majority, was little discussed. The two most important newspapers in the nation, The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, did not run a story.

Religion is dying, and barely anyone has bothered to even note its passing.

It was a big surprise, therefore, when I spoke to actor and model Katie Cleary for the Green Pill podcast and discovered she’s a devout Christian.

I had asked Katie to speak with me about her upcoming documentary, Why on Earth, which features Clint Eastwood and a host of other celebrities as Katie crosses the planet to protect endangered wildlife. And I was taken aback when she shared that her work was motivated by a deep faith in Jesus Christ. This was partly because of my personal experience: Christians made my life hell, when I was a child in Central Indiana, and the avowed atheist and biologist Richard Dawkins has been one of my intellectual heroes. I have had barely any interactions with Christians for the last 20 years of my life. But despite this, conversations with people like Katie have led me to a changed view on faith: I’ve come to, not just respect, but see immense value in religious belief.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that faith improves the lives of believers. Individuals who live in communities with high religious participation are more prosperous, more educated, and even more likely to get married. They are better off in many other ways, and the effects are “sizable” and “robust.”

The starting point of this analysis, for me, was an observation made by Katie during our conversation: her faith helped her through her husband’s suicide. It had not occurred to me that there might be some link between faith and mental health. But Katie’s story shows how faith, by giving purpose even to the most devastating crisis, can insulate people from depression and hopelessness. As she explains, when everything else seemed to be falling apart, she still had God, an omnipotent and benevolent force that would comfort and guide her down the right path.

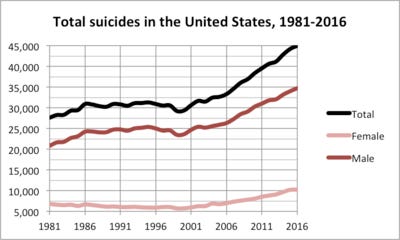

What’s true for Katie, moreover, may be true for many others. Consider these numbers: church membership hovered at around 70% until the year 2000, when it began a steady decline to its current level of 47%. But 2000 was an important year for another reason: it is the year that suicide levels began to skyrocket, increasing by 50% in less than 20 years.

This association between religion and suicide, of course, is not necessarily “causal”; social science is much messier than that. But one prominent economist, Jonathan Gruber at MIT, has done work to show that religion may be causally associated with all sorts of positive outcomes in life, from wealth to education. And the primary mechanism through which this works is quite simple: religion reduces the stress and loneliness of human life. As one scholar put it:

“People apparently need religion to deal psychologically with the challenges of life that they encounter on a daily basis. It gives them hope, meaning, and a sense of purpose.”1

This was very true for Katie. At a time in her life when she had lost, not one, but two of the most important people in her life, faith gave her support that allowed her to not just recover but thrive. As I note in the conversation, she is one of the happiest people I know, despite her life’s tragedies, and she cites faith as the primary cause for that.

Personal well-being, though, is not the main reason for my changed view on organized religion. There is a second and even more important reason: religion builds trust in human communities and allows us to cooperate. To the extent cooperation is necessary for our survival, that implies the death of religion might just be… the death of all of us.

Consider that studies of religious sentiment show that faith is associated with increased generosity, reduced likelihood of cheating, and increased social trust in large human communities. Indeed, an important study in Science Magazine compared religious to non-religious social contracts and concluded that “fully reasoned social contracts that regulate individual interests to share costs and benefits of cooperation can be more liable to collapse.”

Translation: people can’t work together without religion. When they have a shared faith, in contrast — see, e.g., the pro-life movement — they can work together with incredible success even in the face of individual or ideological differences.

The reason? Unlike religious commitments, any secular social contract may be weakened because, as the Science study puts it, “more advantageous distributions of risks and rewards may be available down the line.” It’s therefore easy for people in non-religious contracts to “defect,” i.e., break their commitments and possibly even run off to avoid accountability.

Religion, in contrast, “deepens trust” and “galviniz[es] group solidarity” by tying groups of people to unchanging rituals and values. It’s hard to cheat or steal when you believe an all-knowing God is going to find you wherever you go. Indeed, the authors of the Science study suggest that it may very well be the case, that “big groups” (such as the nearly 8 billion people on Earth) require “big gods.”

This does not mean religion is the solution to the world’s problems. The studies of religion, showing its importance in building social trust and solidarity, also show that religious beliefs can also lead to negative feelings about outsiders to the faith, creating conflict between religious groups. In some cases, this may even lead to support for violence against outsiders, including suicide attacks.

The decline of religious faith, moreover, may be irreversible, even for those who might like to secure its personal and social benefits. As knowledge and information spread, the sacred stories of the great organized religions are coming under increased scrutiny and pressure, such as Dawkins’ best-selling book The God Delusion; organized religion may someday become as outdated as the VHS or flip phone.

And yet the challenges posed to the human condition by conflict and distrust are important enough that even the non-religious should pay heed to the benefits of faith. Perhaps we cannot rely on the church to bring us meaning and community. But then we must build alternative institutions — which provide support, purpose, and community — that can thrive in the 21st century.

Give my conversation with Katie a listen, and let me know what you think.

It’s worth noting that other research on faith’s impacts on happiness is mixed. And it may be the case that faith helps mostly communities where levels of stress are already high. However, as stress increases across the world, even in wealthy countries and communities, religious faith (or some alternative to it) may be increasingly important to well-being.

Interesting conversation. Thank you Wayne and Katie Cleary for sharing such personal stories. I am a militant atheist for separation of church and state. Even before I realized that I didn't believe in god, there was no religious or spiritual community that my family and I belonged to. My family did go to church when I was a kid and then stopped (long story), but they still believed in god. I appreciate that I wasn't indoctrinated into catholicism or christianity. I realized that I didn't believe in god when my younger sister wanted to know what happens when people die, so I got her a book. I told her that these are made-up stories because nobody knows what happens after people die. I don't believe in an afterlife. I don't need faith to be a good person in life.

"Individuals who live in communities with high religious participation are more prosperous, more educated, and even more likely to get married."

I strongly object to the above statement's inherent assumption that being married is somehow superior to being single. For many of us, this is NOT the case. I don't want to ever get married, and I am not alone. Please be more sensitive to those of us who choose alternatives to marriage instead of going with the old notion that marriage is somehow the most desirable state.