A Simple Plan For Transforming Every Slaughterhouse On Earth Into Sanctuary (Part I)

Open rescue remains the most important strategy to end the slaughter of animals. But it faces important obstacles.

In January 2015, DxE launched the Open Rescue Network. The animal rights movement had been arguing to the world, for decades, that animals deserved to be freed from the fur farms, laboratories, and meat production facilities. But, especially with respect to this last category — farmed animals — we were failing to put our money where our mouth was. While we talked passionately about the liberation of all sentient beings, very few people were working to bring liberation to life.

Our open rescue of Mei Hua, from torture at of one of the most prominent corporations in America — Whole Foods — was an attempt to change that. Millions of Americans heard about the horrifying conditions inside so-called “humane” factory farms as a result of that rescue. Our goal, however, was not just short term attention to animal cruelty but the long term growth of a movement for liberation. I wrote about this vision in the announcement of our ambitious roadmap to animal liberation a year later.

While the rest of the world waits for animal liberation, in Berkeley, our motto will be “Liberation in Action.” We will rescue the animals, no matter what it takes. We will bring the victims back into our newly-anointed safe haven city. And we will dare the animal abusing corporations of this world to try us in the court of law or the court of public opinion. The stories we tell of animals rescued from hell will shake the world -- Liberation Pledgers will pledge, mothers will cry, sisters will rage, friends and allies will protest -- and trigger a fierce backlash by Big Ag that will force the nation and world, for the first time in history, to make a choice:

"Do you wish to stand with those who rescue animals? Or those who torture them?"

Rescue, I argued, was not just a tactic but a strategy. It was the defining action of animal rights. Many years later, I still believe that blog and accompanying roadmap are among the most important things I’ve ever taken part in drafting. And many of the aspirations in the original roadmap have come to fruition— and faster than any of us expected.

Two goals, in particular, come to mind. First, we set a goal that, by 2025, an entire class of animal products, e.g., fur, would be banned in a major city or state. In fact, this was much too pessimistic. After earning support from key legislators by, using footage of rescues we shot from inside animal-abusing facilities, we successfully banned fur in San Francisco in 2018 and in the entire state of California just a year later in 2019.

Second, we set a goal, also in 2025, that hundreds of people would join us in major open rescues at factory farms. We later added to this goal that we would win precedent-setting victories for the right to rescue in court in that same year. Once again, we were far too pessimistic. Our first open rescue involving hundreds of participants occurred in May 2018, when around 500 people joined us in giving aid to animals at Sunrise Farms, a major supplier to Whole Foods. And we won our first precedent-setting victory just a few weeks ago in Utah.

While these victories are important, however, there are other milestones in the roadmap for which we are falling significantly short of our timelines. First, we set a goal that by 2020, a half-dozen independent open rescue teams would be regularly garnering national media attention. It’s not clear that we have even a single team of this sort today. The last investigation that garnered major national media occurred in 2020, and it was focused on ventilation shutdown (VSD), and not rescue. While significant, investigations of cruel practices such as VSD probably lack the power to build a movement. (And, indeed, there has been essentially no grassroots mobilization after the VSD investigation; it was mostly a one-time operation, albeit a very important one.) Investigations, unlike rescue, lack the ability to inspire and scale.

The last major national reporting on open rescue, however, occurred at the end of 2019, when WIRED and the national columnist Ezra Klein both published major features on the rescue of animals from factory farms.

Second, we set a goal that, by 2025, “Open rescue [will happen] so regularly that it becomes a nationally known concept that ordinary people have heard of and a significant issue in national politics. Presidential candidates are asked, ‘Where do you stand on open rescue?’ ” We are far short of this goal. While there has been some national coverage of the right to rescue, the concept is far from nationally-known and, if anything, there has probably been a decrease in attention and understanding of open rescue since the peak of our work in 2018. This is even true within the animal rights movement, which has moved away from frontlines work towards more abstract and ideological campaigns, e.g. corporate reforms or legislative advocacy. It sometimes feels like the movement is back to where it was in 2012 when we launched DxE, except vegan outreach (the dominant form of activism in 2012) has been replaced by legislative and corporate campaigns.

One should not, of course, become too attached to a particular strategy or goal. And perhaps the shift away from rescue and frontlines work was a wise one. But, given the continued power of stories of rescue — most recently, in a powerful feature in The New York Times — and our recent precedent-setting win for the right to rescue in Utah, I suspect that is not the case.

Rescue remains the defining action of the animal rights movement, not just symbolically, but strategically. It fuels the crucial combination of anger and hope that has served as the foundation for movements for the last 200 years of American history. It directly challenges the exploitation of animals, and creates a so-called “decision dilemma” — a situation where an entrenched system of power has no choice but to change — for the industry and government. Rescue, in short, is the embodiment of animal liberation.

So why, then, has rescue declined? There are three reasons I can think of.

The first is that the prosecutions that began in 2018 against DxE have successfully deterred many people from participating. This is especially true given the Left’s unfortunate shift towards what I call safety-ism — a pathological concern for safety that goes far beyond the objective risks that each of us are actually facing. The Left used to be the movement of courage and sacrifice; today, driven in part by social media, it is a narcissistic shell of what it used to be, focused on a narrow conception of self-interest and preservation rather than community health or empathy. That is a hard climate in which to inspire people to take risk.

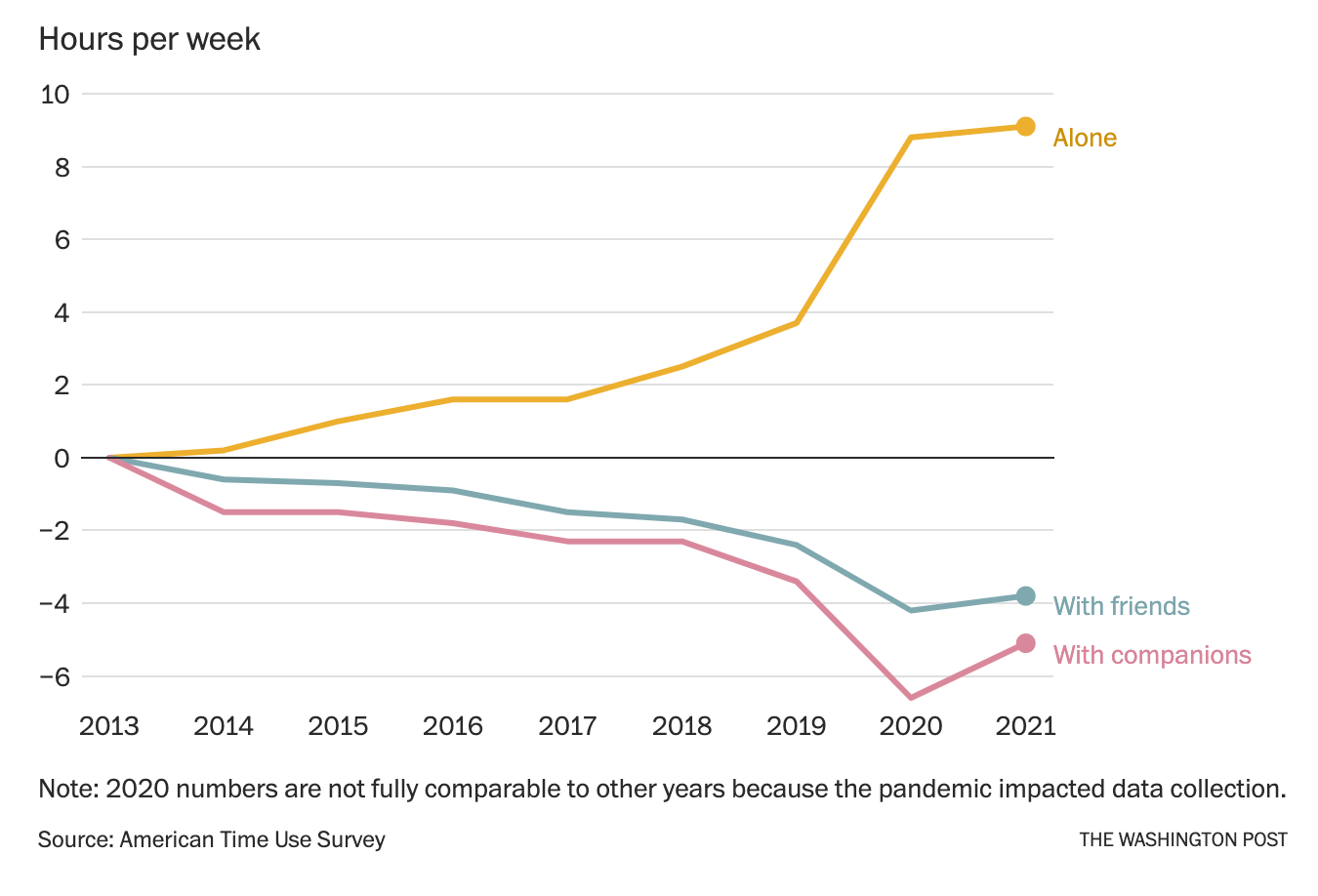

The second reason for the decline in open rescue is COVID-19 and, more generally, the collapse of community. Open rescue, like many forms of powerful political action, is grounded in relationships and social networks; you can’t do it alone. Because the pandemic disrupted relationships, it also disrupted open rescue. According to the Washington Post, Americans are now spending, compared to a 2013 baseline, nearly 10 more hours alone, and 10 hours less time with companions and friends.

It’s worth noting, however, that this decrease in socialization, was already accelerating rapidly before COVID-19. This problem, in short, cannot be blamed entirely on the pandemic. But whatever its cause, the increasing loneliness of the average American is hurting, not just animal rights, but all efforts at collective action, whether on climate change or women’s rights.

The third reason for the decline in open rescue, however, is probably the most important: the decline in trust, and the accompanying increase in civil strife. When we started DxE in 2013, and launched our first open rescue in 2015, we aimed to create a welcoming and warm movement . And while social justice spaces were notoriously cold, especially if you were “different” in some way, there was at least space for a community of the sort we wanted to create.

Today’s world feels very different, with conspiracy theories, rumors, and hostility animating both sides of the political spectrum. That makes it tremendously difficult to organize collective action, as it’s difficult to take risks — or even work together — without trust.

I have seen the impact of the decline in trust in both local and global collective action. Friendships had been broken. Hope has been replaced by cynicism. And the overwhelming feeling, even by those who are just peripherally involved in the movement, is no longer inspiration but fatigue.

On a personal level, I am doing much less work than I did in 2017, when I worked myself to exhaustion and developed a bizarre skin infection due to the collapse of my immune system. Even though I was physically broken, I was spiritually strong; I felt more hope than I’ve ever felt in my life!

The situation today is, in many ways, reversed. I am physically healthier and stronger in 2022 than I have been at any point in the last decade. I am running a sub 5 minute mile for the first time since I was in my early 20s, and I have been sick once — from COVID — in the last two years. Yet despite my physical health, I feel spiritually weak. The reason, in part, is that, after years of conflict, I am much less trusting of the people around me.

These three problems — fear, isolation, and distrust — are combining in toxic ways to prevent movements from creating power. But all is not lost. There are solutions grounded in the lessons of history. And these solutions will not just aid us in building a movement for rescue. They can show us how the movement for rescue can transform every slaughterhouse on this planet into a sanctuary.

I’ll write about these solutions on Thursday. But for now, let me just give you this preview. To build a movement for rescue, and to challenge slaughter, we need to bet back to the basics. We need to get back to the what is perhaps the most fundamental building block of human sociality, and one of the original organizing principles of DxE.

We need to get back to telling great stories.

Hi Wayne. I’m so sorry to bother you I didn’t know how to contact you, and also didn't want to bother you so I thought if it was open comment others could see and maybe help. I adore you and I read all your emails, and I appreciate them so much. I live in the U.K. and desperately want to be exactly like you. How would you recommend I start please? I’m saving up to study law, but I can’t find any open rescue groups in the U.K. I don't know many people and don't have many follows online.

Hello Wayne, Gaia loves people like you. So do I. I've been Vegan for about 65 years.