Why you should spend all your time on Facebook

When you steel-man Big Tech, you get some surprising answers.

In my last 2 posts, I’ve thrown some serious shade at Big Tech and social media. For good reason. There is evidence that social media usage makes people lonely and depressed. Facebook has acknowledged its products may be hurting people, especially younger women. And even going back as far as the year 2000 — remember Y2K? — prominent scholars, including a former mentor of mine, have warned us of the risk of internet echo chambers fueling disinformation and conflict.

Earlier in my life, I was an enthusiastic supporter of tech and social media in the face of these critiques. This is partly due to personal experience. When I was a lonely depressed kid growing up in central Indiana, I had two salvations: animals and the internet. I’ve written and spoken extensively about the former. But tech was in many ways just as important to me as my dogs in making it through hard times. The kids at school made fun of me for being fat, unattractive, and a nerd. But online, I could literally be a hero.

I built my own computer from clearance parts and found community in online forums called IRC (Internet Relay Chat) channels. I became a somewhat prominent competitor in an online video game called Quake. And I made virtual friends in that arena, friends with names like Speedphreak and Jotham. We were a rebellious gang of idealists who were ought to change the world… or at least beat the more well-known Quake teams (called “clans”). And I still remember the glorious moment when we upset the then-best Quake CTF clan, a super team called Clan Venom. Months of training and practice, with me as team lead, had paid off in a victory that was as unexpected as it was exhilarating. People whispered my name in awe after it happened.

It was my first experience with leadership, and really success of any sort, after a lifetime of being a loser. And it one of the reasons, 20 years later, I was able to launch the animal rights network Direct Action Everywhere. Tech helped me understand I have something offer to the world.

So I have many reasons to believe deeply in the power of tech. And yet here I am, today, calling out tech as one of the primary threats to life as we know it. (In contrast, my commitment to animals — my other childhood salvation — has only strengthened.)

The story of what changed for me is a long one. But in this post, I want to take on a different question. What if I’m wrong?

Farhad Manjoo, a columnist I respect at the New York Times (among other things, he made a post a few years back admitting that “the vegans are right”), recently wrote a piece arguing that the concerns over social media, triggered by the recent Facebook whistleblower, are becoming a moral panic. And it’s true that there’s a long line of media platforms that have triggered exaggerated fears in the public. Romance novels, comic books, violent movies, and video games. Each was once described as an existential crisis in the human condition; each turned out to be nothing of the sort.

So we have two plausible theories: (1) social media is isolating, depressing, and even killing us; and (2) social media concerns are a moral panic.

To sort out the two theories, we have to look to evidence. And in this post, I want to make the strongest case, based on evidence, that social media is good for our society. This is part of the spirit of the blog: steel-man the positions you oppose to test the soundness of your beliefs.

To get things right, you always start by making the strongest arguments for why you might be wrong.

So how do we steel-man social media? Let’s go with evidence form the company that has perhaps the strongest incentive to make social media and tech look good: Facebook. This isn’t going to be a deep dive, but even the results of this shallow dive are going to be very surprising.

The recent exposé of Facebook, that led to congressional hearings and a dramatic appearance by a whistleblower on 60 Minutes, has focused on the damaging impacts of social media on the people who use it. The Wall Street Journal, which first broke the story in a series called “The Facebook Files,” describes it this way: “Facebook Inc. knows, in acute detail, that its platforms are riddled with flaws that cause harm, often in ways only the company fully understands.”

The headline of their most dramatic article in the series, makes the single most damning allegation: “Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Many Teen Girls, Company Documents Show.” To quote the piece:

About a year ago, teenager Anastasia Vlasova started seeing a therapist. She had developed an eating disorder, and had a clear idea of what led to it: her time on Instagram.

“When I went on Instagram, all I saw were images of chiseled bodies, perfect abs and women doing 100 burpees in 10 minutes,” said Ms. Vlasova, now 18, who lives in Reston, Va.

Around that time, researchers inside Instagram, which is owned by Facebook Inc., were studying this kind of experience and asking whether it was part of a broader phenomenon. Their findings confirmed some serious problems.

“Thirty-two percent of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse,” the researchers said in a March 2020 slide presentation posted to Facebook’s internal message board, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. “Comparisons on Instagram can change how young women view and describe themselves.”

Reading the piece, it’s hard not to get angry. One in three teen girls is tens of millions of American children being harmed! The public narrative in the media and in Congress reflected this anger and made a compelling case to bring down Big Tech. These were products as dangerous as cigarettes; indeed, the comparison to Big Tobacco was made very explicitly by Frances Haugen, the former Facebook employee turned whistleblower.

But, little noticed, the company released the purportedly confidential files that the Wall Street Journal had uncovered. And a review of these source files, and especially the key slide on page 14 (see below), paints a very different story from the one that has been reported.

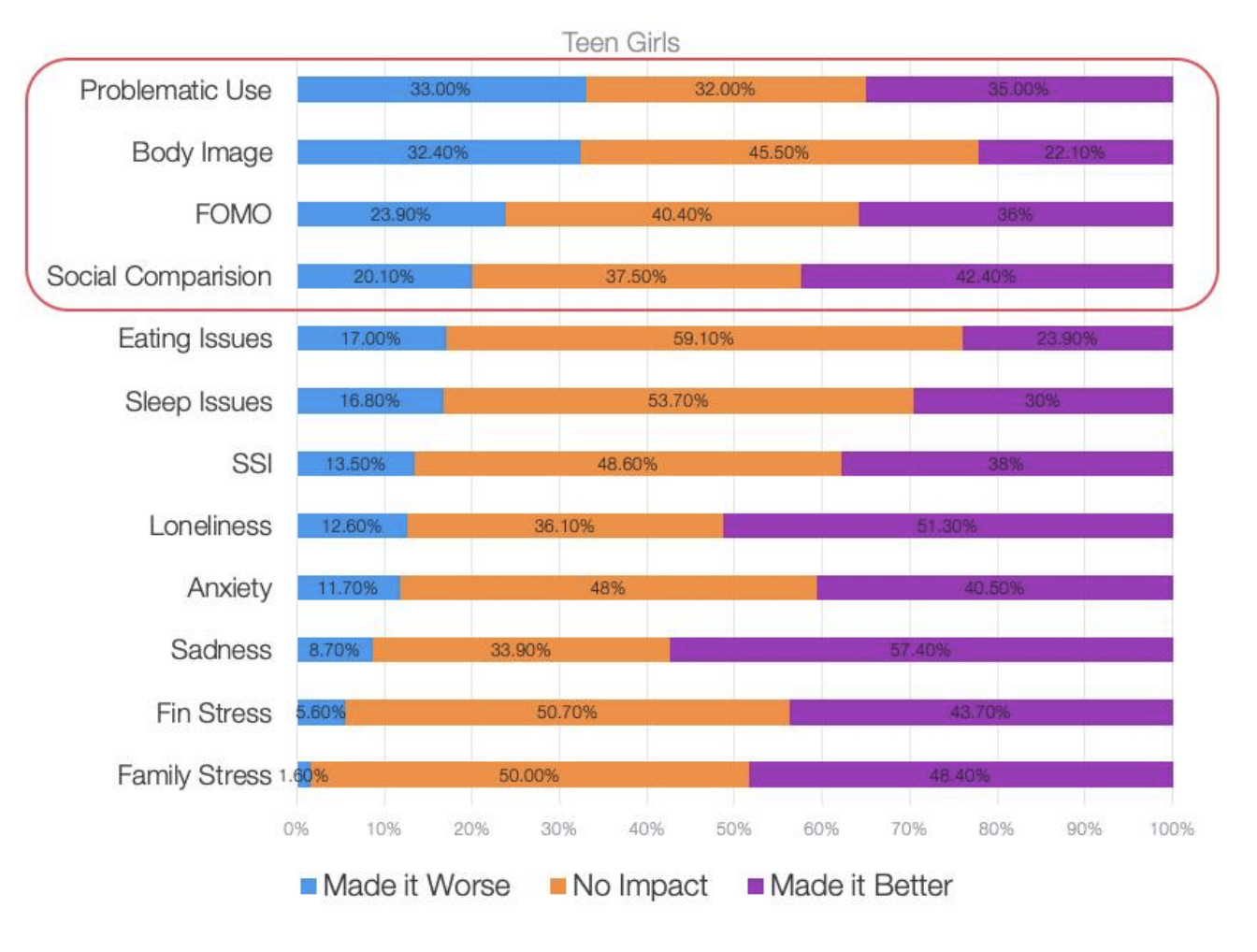

For one, the WSJ and other media stories fail to point out that, while it’s true that 32% of young girls say that Instagram made them feel worse about their body, 22% said that Instagram made them feel better and 45% said it had no impact at all. (See the second line of the chart above.) These data points were left completely out of the story, which could have had an alternative headline: “Vast majority of young girls say that Instagram has no impact or helps them with body image issues.”

But perhaps even more importantly, body image was just 1 of the 12 categories of mental health examined. And in the other 11 categories, Instagram was reported as being supportive of teen health. For example, a whopping 57% of young girls said that Instagram was helping them with sadness while only 9% said it was making their sadness worse. And 48% of young girls said Instagram helped them with family stress while only 1% said it made things worse. Based on the same data the Wall Street Journal used to conclude that Instagram was “toxic” to young girls, one could write a different headline: “In over 90% of mental health categories, Instagram is helping teen girls — and often overwhelmingly so.” Indeed, in the spirit of steel-manning, that alternative headline is probably a more accurate representation of the data.

I wish I could say the discrepancy between (1) the media accounts; and (2) the reality were unusual or surprising. But it is not. Too often, journalists go into a story with a fixed mindset about the conclusion they want to draw. (I have lots of experience with this.) Moreover, saying “things are fine with Instagram” doesn’t sell ads or subscriptions. Modern media, through the very algorithms that the WSJ has condemned, often goes for the most anxiety-inducing narrative, regardless of whether it’s true. The Wall Street Journal’s own exaggerations, in short, are a surprising example of the very phenomena that they are trying to condemn: disinformation incentivized by the competition for users’ attention.

The upshot, for me, and for anyone else who is trying to get at the world the way it is (whether for our own integrity, or to enhance our ability to create change) is this:

The danger Instagram poses to young girls, at least based on this one study, is greatly exaggerated. And once I opened myself to that possibility despite repeatedly sharing the WSJ investigation as gospel, I have opened myself to others, too. For one, the internal “studies” showing dangerous impacts on young people are hardly studies at all; they are just self-reported surveys. And it’s widely understood that self reports are unreliable and susceptible to bias and manipulation.

For another, the fact that Facebook was even doing such research, and including some possible dangers of their product within it, is a sign that the employees who did the research probably had good intent. Condemning them for pointing out possible weaknesses in their product, especially when they subsequently release the research openly, seems like a terrible precedent to set!

Where does that leave us? I’ll suggest 3 takeaways. First, what this discussion should not do: it should not change your minds about the impacts of social media. Phil Tetlock, perhaps the world’s foremost expert on good judgment, has generated evidence that people who make sound decisions don’t change their minds in dramatic ways . Instead, people with good judgment change their minds frequently, but in small ways, recognizing the limitations of any one piece of data. Given the quality of the data at issue, especially, the weakness of the WSJ exposé should never have moved us too much in the direction of hating Facebook. That does not mean there aren’t other reasons to believe Facebook is causing harm, just that this one data point should not have changed our minds too much.

The second takeaway is that we need to dive more deeply into issues we want to form legitimate opinions about. What I’ve found over the last 20 years, from my time as an intern and aspiring journalist at CNN, is that not just the media, but people in general, stay at the surface level on most issues. It’s one of the many reasons why those who dive deep can make an impact. There are countless examples I can cite from my own life.

When the majority of the animal rights movement believed 10 years ago in the primacy and efficacy of vegan outreach, I dove a little deeper and found that most of what was being said was bad science. (I faced serious punishment within the movement for pointing this out, but that’s a subject for another day.)

When the movement shifted to focusing on cage-free eggs, supported by millions of dollars from billionaires with little expertise in farm animals, I went through the actual literature and found things that were very different from what was being said. (I faced slightly less punishment for disagreeing with this element of the movement canon, and at least one prominent funder of this work updated their beliefs — though in my opinion, far too mildly — as a result.)

These dives were not really a product of any unique intelligence or creativity. (Most of what I discuss above is pointed out in Facebook’s own statement!) I was just one of the very small number of people who dove a little deeper and reported what I found.

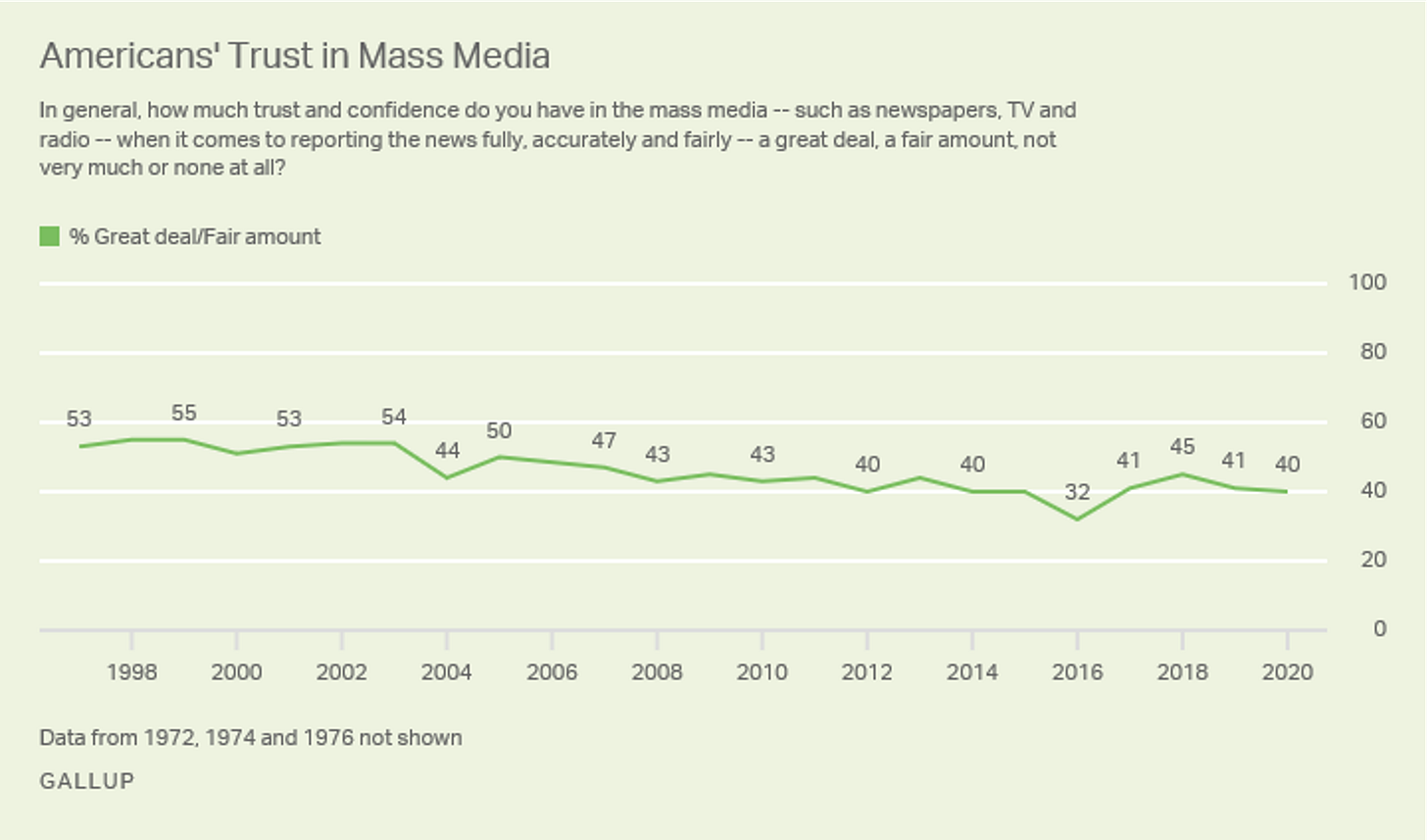

The third takeaway is that we should be less trusting of the media. I don’t want to be an alarmist. I don’t think there has been a sudden decline in media quality driven by corrupt plutocrats, as some have suggested. And despite some fear mongering, public trust in the media has not suffered a precipitous decline. Trust in media has actually been going up slightly and was at its lowest point in 2016. But the fact of the matter is that the media is a business, and as a business, its north star is profit, not truth. And if the Wall Street Journal — one of the best and highest-integrity newspapers in our nation — can say false things about Facebook, and create a firestorm with little accountability, then that probably means other media is saying even more false and exaggerated things with impunity.

I don’t mean to leave you all in a depressing place. In fact, I think there’s a positive side to this story. Indeed, that is part of the reason I started this blog. Because if we do create a more skeptical culture, and we place trust where we should place it (not in the media, but in institutions that don’t have the incentive to exaggerate or tell a preconceived story), then I think we can find a path to better answers. But that’s the subject for another blog. In the meantime, I hope you found this analysis interesting — and it helps you see, in some small way, why I think the project of this blog is important.

In the spirit of this blog, consider reaching out to someone you know, in person or over the phone, and sharing something you learned. Better yet, invite a group of friends over to discuss your collective social media use. Here are some questions you might ask:

How does social media affect my well being?

How does social media affect the way I interact with others?

How does my life change when I am using social media, and when I’m not?

What’s the right usage of social media for me?

What’s the right usage of social media for the world at large?

My 6th grade math teacher told us that paper back books will destroy civilization and that the Beatles were a passing fad. Many of us would not have learned about the cruelty of the dairy and egg industries if it weren't for Facebook, and I wouldn't have learned about DxE if it weren't for Nextdoor. I think social media can be one of many tools to change society.