The One Word That Can Solve All the World's Problems

Trust.

Human beings are not particularly strong, or particularly fast, compared to other animals. We don’t have sharp claws or hard shells. We’re not even very good at protecting ourselves from normal weather events, like rain or snow. So how have we become the most successful species on earth? There are a lot of explanations, from our large brains to our opposable thumbs. But there’s a one-word answer that I think explains our success better than any other:

Trust.

For the last 50 years, the General Social Survey (GSS) has defined trust with the following question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’’ And the answer to this question is crucial to our species’ success.

Why is trust so key?

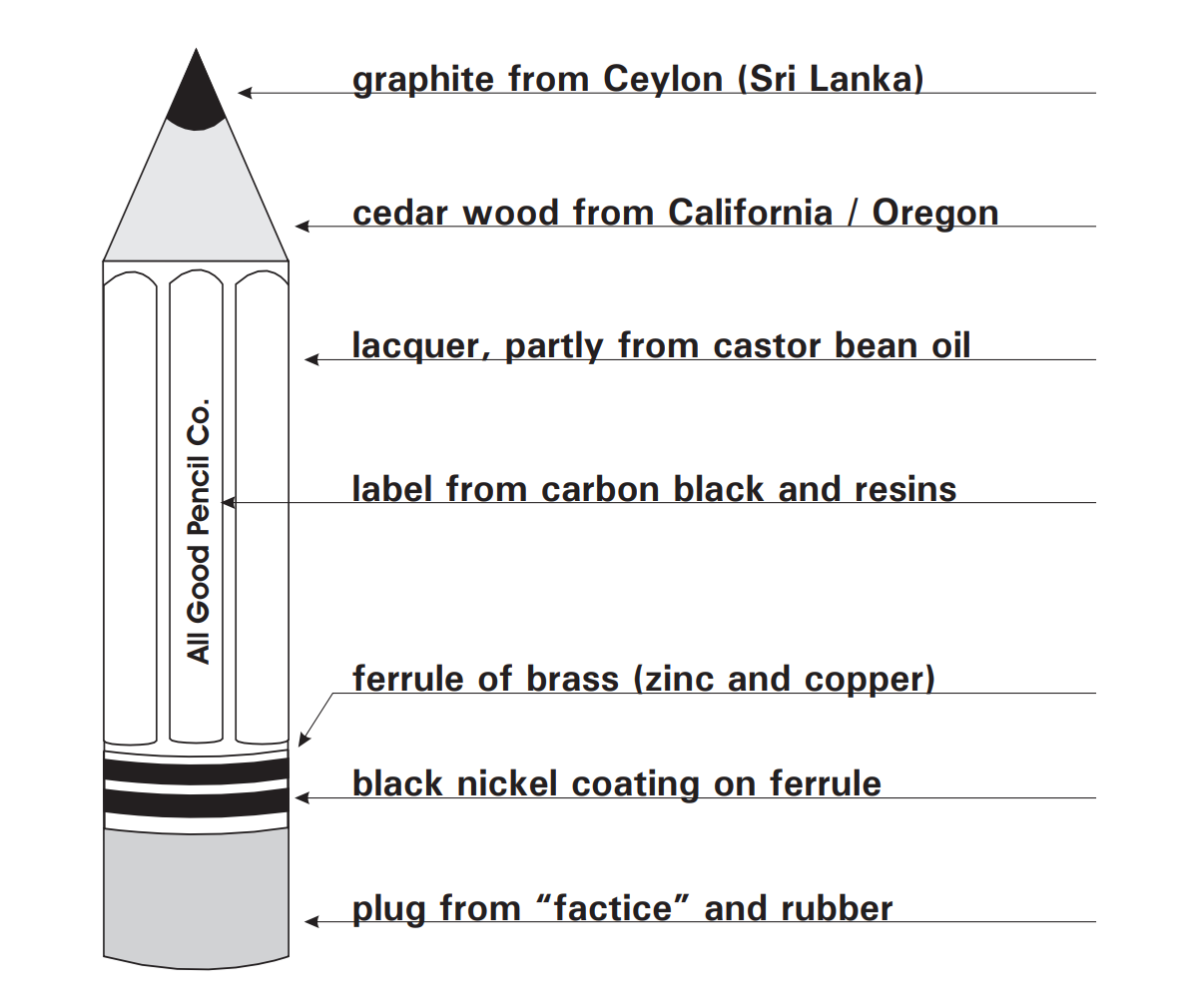

Trust allows us to cooperate, and achieve things that would be difficult for any one person to achieve. Consider the number of people it takes to make a common pencil.

Each of the people involved in this production must trust someone else to continue the process. But the result, when cooperation is achieved, is extraordinary. We are able to find or develop new food sources, as with the so-called Green Revolution which used novel agricultural methods to save over 1 billion people from starvation. We are able to build communications infrastructure, such as the modern internet, that would seem like magic to human beings just a generation ago. We can make extraordinary things happen, through cooperation. So it’s not surprising that other high-cooperation species, such as ants and termites, have also experienced astonishing ecological success.

Trust also allows us to invest into the future. Most animals live in the present. They can’t do things that would have huge payoffs, if those payoffs don’t come until months or years later, because someone might take the fruits of their labor. This is the case with the invention of agriculture. What good would it be to spend months toiling in a garden, if your neighbor just walked into your yard and stole all your fruit the moment it became ready to pick?

Finally, trust is necessary for well-functioning institutions, which can determine a nation’s economic or political fate. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Kenneth Arrow argued that levels of trust in a society predict its economic success. And trust has been shown to be correlated with judicial efficiency, reduced corruption, and governmental competence. It is very hard to build any successful, long-term organization, much less an entire society, without trust.

And yet that is exactly where we are, as a nation: without trust. Recall the trust question in the General Social Survey; in 1972, people were split half and half between trusters, i.e., those who said “most people can be trusted,” and non-trusters, i.e., those who said “you can’t be too careful when dealing with people.”

By 2018, however, things got much worse; the non-trusters outnumbered the trusters 2:1. Separately, Gallup polling in the last few weeks shows that trust in American institutions has reached historic lows; indeed, trust in literally every American institution in the poll is declining. And as Jonathan Haidt argues in The Atlantic, this distrust has made the last 10 years of American life “uniquely stupid.”

Something went terribly wrong, very suddenly [in the 2010s]. We are disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth. We are cut off from one another and from the past.

It’s been clear for quite a while now that red America and blue America are becoming like two different countries claiming the same territory, with two different versions of the Constitution, economics, and American history. But [what is happening in America] is not a story about tribalism; it’s a story about the fragmentation of everything. It’s about the shattering of all that had seemed solid, the scattering of people who had been a community. It’s a metaphor for what is happening not only between red and blue, but within the left and within the right, as well as within universities, companies, professional associations, museums, and even families.

What specifically went wrong? Haidt argues that there are three problems that have caused us to become stupid. First, we lost faith in the shared stories that bring us together — the Judeo-Christian narrative, the idea of American exceptionalism, the belief in Western democracy. Second, we lost confidence in the institutions that employ us, educate us, and even those that keep us alive, such as food and health care. And third, we lost our sense of community; we see our neighbors as strangers or threats, rather than potential allies and friends.

In short, we lost trust. And it’s not just making us “uniquely stupid.” It’s tearing our nation apart. As Haidt put it, it’s causing “the fragmentation of everything.”

Many have felt this declining trust, and increasing fragmentation, in our personal lives. Let me use a personal example, of a friendship I had with an unhoused man in SF that went bad.

On the day I was moving in to SF in early May, Priya Sawhney, who was helping me with my move, met an unhoused person on the street outside my new apartment, who I’ll call “James.” In the time it took me to park my car and return, Priya had convinced James to help us move things into my apartment. I arrived to find James, a young man, with bloodshot eyes and disheveled and dirty clothes, at my new home with Priya. But despite his appearance, he was really helping out — moving large things that were too unwieldy for Priya or I to move alone.

Asking a homeless person to help you move into your house is not a typical thing to do, but Priya is not a typical person. Many would have felt endangered by James. He looked like (and in fact was) on drugs. We later learned that he has an extensive criminal history. But Priya’s act of trust had powerful impacts for many months.

James would say hi to me every time I passed by, which was almost daily. His friendliness made a street with regular police and ambulance sirens feel a little safer. I offered him food or a glass of water, every few days, and he happily took everything I gave. He introduced me to other people living on our street and gave me a sense of community with the local unhoused population. He even returned my keys, when I stupidly left them hanging out the door – not the wisest thing to do in a city with as much property crime as San Francisco. (Try leaving something remotely valuable in your car in SF for 15 minutes, and you’ll see what I mean.) I started envisioning James as not just a friend, but as a potential collaborator in The Sanctuary Initiative. Priya’s act of trust was making all of our lives better, in a way that social science would predict.

But then distrust creeped into our relationship. The first instance came when James asked if he could store things at my home, including a large bundle of unknown contents. While there were obvious reasons he needed the storage space — he was unhoused, after all — James’s tone and body language made me feel uncomfortable. I started to worry that I was storing meth or fentanyl. I didn’t trust him. When he took the bundle back, a few days later, I was relieved. “He just wanted to get his stuff off the street for a few days,” I thought to myself. “Maybe because of the weather or the rain.” But I wondered: did he recognize my distrust?

Then, one evening around 1 am, I heard loud knocking on my door and saw someone jumping up to peer through my window. For a moment, I thought I was being robbed, or perhaps raided by the police. Then I heard James’s voice.

“Hey Wayne! Open up!”

I opened the door and saw James in terrible shape. His pupils were as wide as golf balls, and he was panting, as if he had just sprinted to my door. I thought his arm was broken because of the way he was holding it against his side. And his body was making frantic movements that seemed almost involuntary, jerking to the left and right.

“They’re trying to get me. You’ve gotta let me in.”

Instinctually, I obliged.

“They’re saying that I assaulted a security guard. But I didn’t do it,” James explained. “He was telling me to get out of the park, and I just yelled back at him. I didn’t assault no one.”

I didn’t see any police cars outside. In fact, it was deadly quiet.

“I know people in the SF public defenders’ office. They’re good lawyers,” I said.

“I’ve already got a public defender, but they don’t return my calls,” James replied.

“You can change your attorney if they don’t reply. Let me help.”

I gave James my number, and told him to send me more details: the nature of the offense, and the attorney who was supposed to be representing him. I said I would help him find counsel, if his attorney was unresponsive, so he’d be able to address the charges instead of fleeing from the police. He agreed.

And then he was off into the night.

For the next few days, I didn’t see him. I wondered what had happened, and why he hadn’t texted or called. I thought about reaching out to the public defenders’ office anyways, or even looking through the court system to find his case. But I didn’t even know James’s last name.

Then, one night at around 10 pm, James suddenly appeared. I didn’t notice him at first, as he was turned in the other direction in a small alley about 100 feet from my apartment. I was taking my dog Oliver to my car, for a ride to the local dog park. I do this late at night because of the trauma Oliver endured in the dog meat trade. Oliver is terrified by strange people and sounds.

Oliver and I both heard a loud voice from the alley.

“Yo, Wayne!” James shouted.

Oliver responded by immediately lowering himself to the ground, pulling his ears back, and jerking hard on the leash away from the voice. There was terror in his eyes.

“I need your help,” James said.

“Did you get my number? Can you call me or send me a text?”I said. I was struggling to control Oliver as he pulled away.

“I lost my phone, man. I need your help!”

Oliver had spun the leash around my legs and was cowering and pulling away from James. I was afraid he’d knock me over and run off into the SF streets.

“I’ve got my dog, and I’ve gotta go,” I yelled while trying to untangle Oliver and get him into the parking garage, where he’d feel more safe.

James looked angry.

“Yo, I see how it is. You forget your brother already?”

“No I’ve just gotta walk my dog. He’s scared. Let’s talk when I get back.”

I walked through the door to the garage, and heard a faint voice through the wall from the other side. It sounded like, “Fuck you.”

James was gone when I came home. And to this day, I have no idea what happened to him.

The situation has left me feeling uneasy, and even a little unsafe. I don’t feel James would intentionally hurt me. He’s a good man with big problems, legal and otherwise. He confided in me that he had a drug problem, and a criminal history. “Sometimes going to jail is the only way for me to get clean,” he once said. But I’ve worried that he might act rashly towards me, or Oliver, out of desperation rather than malice.

Hurt people hurt people.

I was also stunned by how quickly things went bad. After months of only great vibes, built on Priya’s initial act of trust, it all went downhill in a matter of days. “Trust is hard to build, easy to lose,” I’ve thought to myself. And a couple confusing interactions was all it took to shatter the trust we had built.

The hardest thing is that I understand James’s distrust. I had not been straightforward with him about storing his property; I should have just told him I didn’t want to hold it. I had probably over-promised when I said I’d find him counsel; perhaps he thought I owed him a text or phone call to update him on my efforts to help him find a lawyer. And, finally, I had failed to convey to him why I cut short our conversation, when he was desperately in need on that last night. To him, I am sure, it showed my true colors: happy to be his friend when it didn’t cost me anything, but ready to jump ship the moment things got rough. Perhaps there’s truth to that belief. I don’t want to believe it about myself, but I am sure I felt frustration and even fear, as James’s life was going south. I blamed him for his problems rather than trying to understand why he was struggling to survive.

But whatever the cause, or the respective blame to go around, the streets outside of my apartment now feel a little less safe. The feeling of cooperation James and I had, from the day I moved to SF, is gone. We’re not working together to keep the streets fun and safe; that feeling has been replaced by low-key discomfort and even fear. My desire to build a community center in this apartment is not as high; I’m less inclined to invest in something that would benefit both James and I, in the future, because of our loss of trust. And the hope I had when I first met James, of having him join TSI in building a better community for all, now seems like a fantasy. Indeed, I’m less optimistic about the potential of any people suffering James’s plight — addiction, homelessness, and a criminal history — to be involved. The institution I was trying to build has suffered because of distrust.

The fall of my friendship with James, however, is just one example among many, of human relationships that are falling apart from distrust. Perhaps most disturbingly, however, is the fact that distrust is not just an individual problem. It has catastrophic systemic consequences on cooperation, investment, and institutions across the globe.

Lack of trust, for example, is one of the biggest roadblocks to solving the climate crisis. Why would I sacrifice driving my fossil-fuel based car, or eating my delicious hamburger, if I can’t trust you to do the same? It’s pointless to sacrifice for the climate when I don’t trust others to do the same. Global conflicts such as the Ukraine crisis are also conflicts of distrust. Putin, and the Russian people, do not trust that the West has good intentions, in encroaching on their borders. The US, in contrast, felt the need to expand NATO to Western Europe in part because it did not trust Russia’s plans.

So how do we do better?

As with all major change, it starts with a vision. And with the launch today of The Sanctuary Initiative, Priya, Dean, and I have a very simple vision for how to solve the problem of trust — and prevent countless interactions like the one I had with James from going bad. Here are some of the key insights from our vision and theory of change.

The first insight is that all trust starts with community. When James and I were working together trying to address shared problems — my need for help moving, his need for food and drink — with a common set of friends, our trust was strong. Indeed, the power of community — a shared physical space with shared relationships — was so strong that, even though he was a complete stranger in a place known to be dangerous, I trusted James instantly, as if he were a long-time friend.

But the truth is that our community was not that real. While we lived in the same general area, we were not actually sharing the same space. He lived on the street; I lived in an apartment. We shared one common friend — Priya — but Priya lives in Berkeley and has only seen James a few times since that first encounter. The physical and social ties that bind people together in community simply didn’t exist with James and I.

What’s true of James and I, however, is true of so many other relationships. With religion declining, civic organizations disappearing, and apartments growing larger and more faceless, very few people have any real community left in life. Community is where trust is developed and learned, in small groups of people who all know each others’ stories and names. And we must create space for community, for its own sake, if we want trust to be restored.

The second insight is that, for trust and community to scale, we need shared values. One of the primary difficulties with James and I was that we had no shared principles to rely on. That led to communication problems — I thought I was just helping my dog feel safe, as an animal rights person, while he felt I was blowing off a friend in a time of need — but it also prevented us from feeling the deep sense of kinship human beings develop from not just working together, but sharing the same purpose in life. A lot of the things we did together — eating, moving things — were not fundamental to our purpose in life. If James had in fact shared some of those deeper values, e.g., if he believed in animal rights, it would have created a much stronger sense of kinship and trust.

Finding shared values is crucial for trust to scale. Community can serve as the foundation for trust in small groups; indeed, community must be the foundation for trust in small groups. But community — shared physical spaces, shared relationships — can’t scale beyond 150 or so people. People lose the capacity to even recognize each others’ names when the numbers get too big. In contrast, shared values can bind people together in large numbers; they can even create affiliation between people who’ve never met. This is one of the reasons religions have been such powerful forces for human organization. Shared religious values allow billions of people to work together. To solve the problem of trust, at scale, we need to instill shared values beyond a single community of 150.

But what if people don’t share the same values? How do we convince them to cooperate, to invest, and to build institutions together?

That leads to the third insight: people across all walks of life can be inspired by radical compassion. Kindness to others. Honesty. Concern for the community. These are all values that virtually all human beings believe in, and that have animated all the world’s major religions. Indeed, they may very well be programmed into our very DNA. But too often, without narratives to inspire our compassion, and leadership to reaffirm it in our actual communities, distrust destroys our ability to actually live with kindness in our everyday lives. Why should I be kind to others, for example, if they are just going to use my kindness against me? To solve the problem of distrust, we need values and narratives that can inspire us to be compassionate, even when it’s hard, and leaders who can coach us in living up to those values.

There is so much more to say about these insights, and how we can harness them to build a better world. But I’ll end this blog post with a simple suggestion:

Help build a little more trust and compassion in the world. We are going to start with a very simple framework:

Find a small group, ideally one that you can meet in person;

Join us as a group in a weekly activity, that’s meant to make your life (and the world) a kinder, more connected, and more trusting place;

Send us updates on how you did.

The activity could be writing to thank or express gratitude to someone you love. It could be asking your friends to join you in a vegan meal. It could be committing to meditate every day for a week. We’re going to choose the activities together — here’s the survey for this week, which I encourage you to take — and that activity will become the focus of the Friday blog post. But regardless of the specific choice, the key thing for all the activities is that they will help us build a kinder, and more trusting, world.

That is especially important to me now because, in a little more than a month, I could be behind bars. There are few places more disconnected, and more distrustful, than a prison. But I plan to join you all in doing this weekly activity even if I am behind bars. It will not just be a lifeline to the rest of the world. It will show the forces that are trying to destroy us, with disinformation and distrust, that they can’t stop us from changing the world. They can’t stop the power of trust.

—

Some other updates:

If you want to learn more about the ideas in this blog, join The Sanctuary Initiative launch party — and my “going to trial” party — tonight (Friday) at 7 pm. The trial has been delayed for a month. But given that we already scheduled this, we are going to keep the date. I’ll be explaining how I plan to stay in touch with you if I’m incarcerated, which relates to a big change to the podcast and this blog. It’ll be a good time, and I hope you can join — ideally in person, but by Zoom if necessary. Reply to this email, if you want to join virtually, and we’ll add you to the WhatsApp. Here’s the event page.

The court denied our motion to question the Costco CEO at trial, among other witnesses. I livestreamed about this on my page. This is another example of the system working to protect wealth and power. This is a blow to our defense, but just remember: the real trial is unfolding in the court of public opinion. So while we won’t be allowed to challenge Costco in court, we can still do it together in our everyday lives.

Don’t forget to take our survey for next week! The big change is that this week, we’ll select not just a blog topic, but an activity. We’ll also be getting your feedback on the strategy we have to build a decentralized network of people, committed to values (such as radical kindness) that can change the world. Take one minute and take the survey!

Thanks to everyone who’s offered support as we continue the fight in court. I’m still very behind in responding to emails and comments. The unexpected, crucial hearings over the last 2 weeks have taken over my life! But for the first time in the last month, we have no case-changing hearings scheduled until trial, which starts on October 3. (If you want to come to trial to support, check out this event page.) I 100% promise that I’ll do that by the end of the week.

That’s all. Until next time!

People shouldn't be living on the streets, especially in the USA, rich country. That is the elephant in the room that the writer is treating as normal.

Here it is again: regarding your trust of a street guy addicted to drugs, I can't trust someone under the influence who's unpredictable and bigger than me. I'm 83 and 49 years' clean and sober (and vegan that long.) I supported a houseless woman who entered a recovery program and in less than a year she found housing, a job and a loving partner. I'm an animal rights activist who got inside a factory farm and filmed. I don't think we're a successful species, but won't give up hope and dedication to freeing the animals. We are not a successful species, where did you get that? Bonobo Pygmy Chimps are successful -- they are matriarchal and don't go to war. The humans who live in Blue Zones are successful. Please examine cultures around the world and do examine religions -- most of them sacrifice animals. Go ahead and trust others, but be mindful of consequences.