Making Friends with Fruit Flies and Other Strange Stories from Jail

On the virtues of dislocation

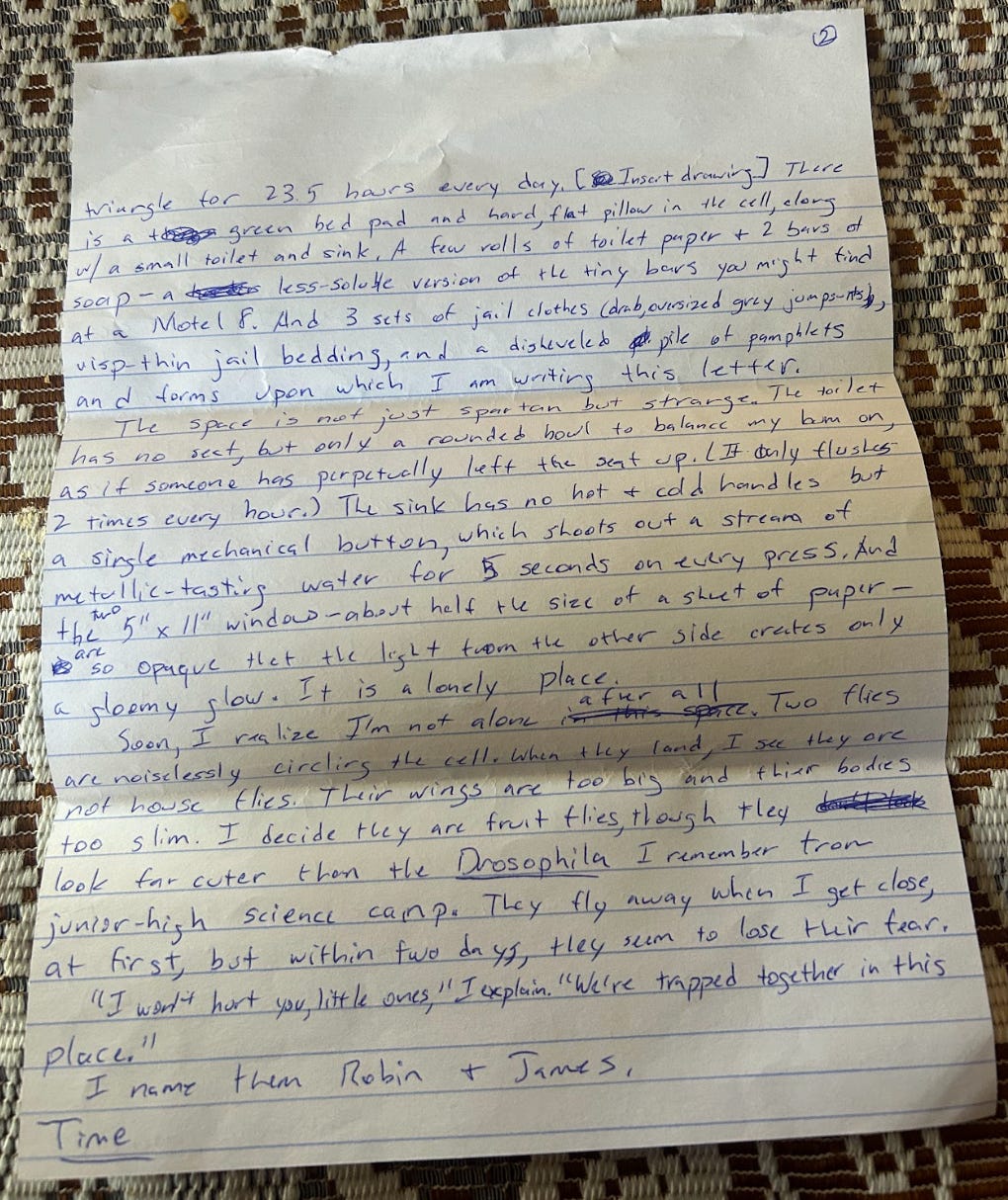

When the journalist Ezra Klein asked how I went from the highest rungs of academia to crawling into slaughterhouses under cover of night, I gave him a one-word answer: dislocation.

Separated as a child from my extended family by thousands of miles; thrust into a PhD program at MIT at the age of 19; and utterly incapable of navigating the social currents as a young academic at 25… I always felt trapped in the wrong place.

But it was precisely because of this dislocation that I was willing to take risks. Doing things that seemed frightening to others didn’t seem that bad when everything in my life already felt so wrong.

Now I face dislocation again. I am trapped in a 50 square foot concrete space for 23.5 hours a day; two fruit flies are my only friends. The days pass aimlessly, with no clocks or sunlight to orient me in time. I have no control over my movement, beyond pacing back and forth. And my connection to everyone I love has been broken, save for 30 minutes each day when I can come out of my cell and get in line for a collect call.

I face dislocation in space, time, connection, and control. Yet, as before, I believe this dislocation will have purpose: by seeing what is wrong, it will also show me (and perhaps others) more clearly what is right.

Space

For the past week, I’ve lived in a solitary concrete triangle for 23.5 hours every day.

There is a green bed pad and a hard, flat pillow in the cell, along with a small toilet and sink. A few rolls of toilet paper and two bars of soap — a less soluble version of the tiny bars you might find at a Motel 6. And three sets of jail clothes (drab, oversized gray jumpsuits), wisp-thin jail bedding, and a disheveled pile of pamphlets and forms upon which I am writing this letter.

The space is not just spartan, but strange. The toilet has no seat: only a rounded bowl to balance my bum on, as if someone has perpetually left the seat up. (It flushes only 2 times every hour.) The sink has no hot and cold handles, but rather a single mechanical button, which shoots out a stream of metallic-tasting water for 5 seconds on every press. And the two 5 by 11 inch windows — each about half the size of a sheet of paper — are so opaque that the light from the other side creates only a gloomy glow. It is a lonely place.

Soon, I realize I’m not alone after all. Two flies are noiselessly circling the cell. When they land, I see they are not house flies. Their wings are too big and their bodies too slim. I decide they are fruit flies, though they look far cuter than the Drosophila I remember from junior high science camp. They fly away when I get close, at first, but within two days, they seem to lose their fear.

“I won’t hurt you, little ones,” I explain. “We’re trapped together in this place.”

I name them Robin and James.

Time

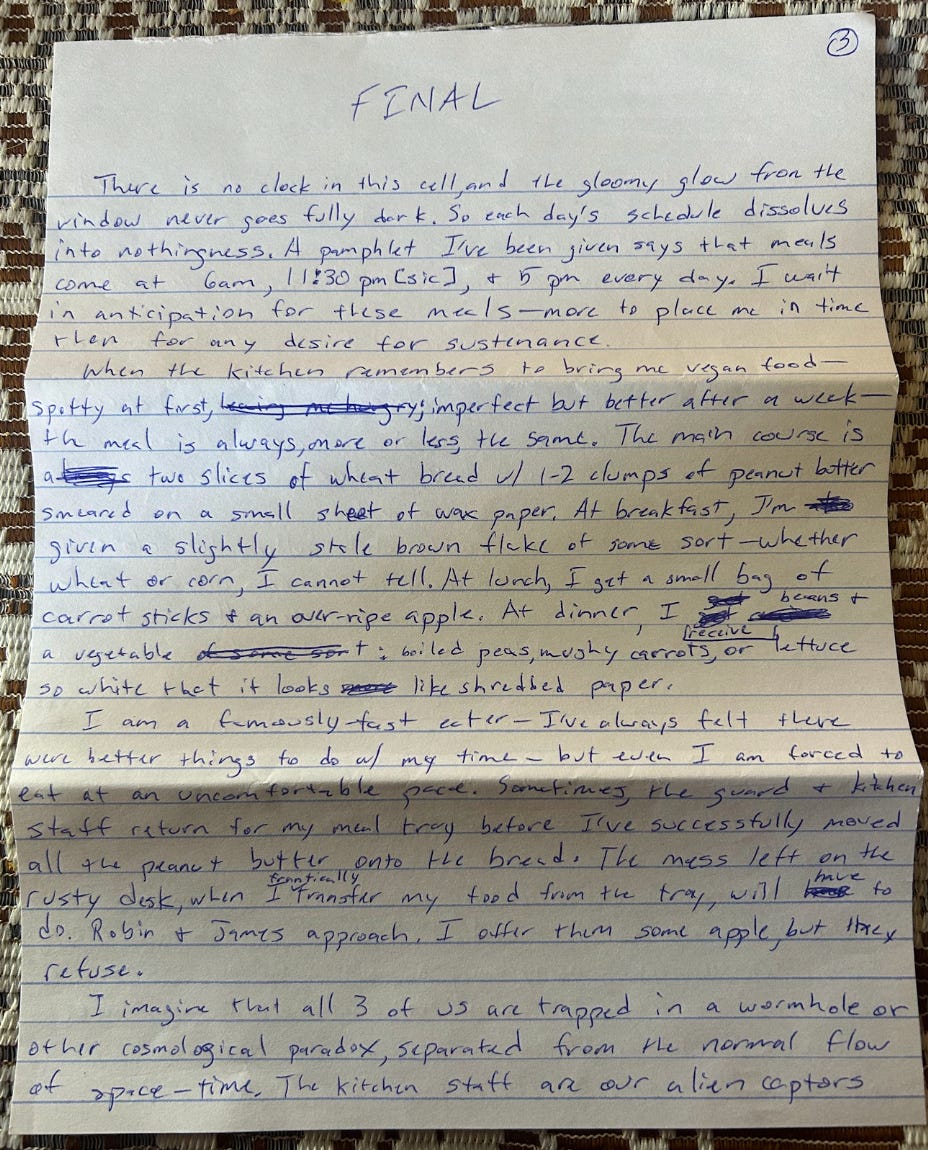

There is no clock in this cell, and the gloomy glow from the window never goes fully dark. So each day’s schedule dissolves into nothingness. A pamphlet I’ve been given says that meals come at 6am, 11:30pm [sic], and 5pm every day. I wait in anticipation for these meals — more to place me in time than for any desire for sustenance.

When the kitchen remembers to bring me vegan food — spotty at first, and imperfect, but better after a week — the meal is always more or less the same. The main course is two slices of wheat bread with one or two clumps of peanut butter smeared on a small sheet of wax paper. At breakfast, I’m given a slightly stale brown flake of some sort — whether wheat or corn, I cannot tell. At lunch, I get a small bag of carrot sticks and an over-ripe apple. At dinner, I receive beans and a vegetable: boiled peas, mushy carrots, or lettuce so white that it looks like shredded paper.

I am a famously-fast eater — I’ve always felt there were better things to do with my time — but even I am forced to eat at an uncomfortable pace. Sometimes, the guard and kitchen staff return for my meal tray before I’ve successfully moved all the peanut butter onto the bread. The mess left on the rusty desk, where I frantically transfer my food from my tray, will have to do. Robin and James approach. I offer them some apple, but they refuse.

I imagine that all three of us are trapped in a wormhole or other cosmological paradox, separated from the normal flow of space-time. The kitchen staff are our alien captors who visit us to perform experiments three times a day. I laugh and wonder if any of us — Robin, James, or me — will survive this other-worldly test.

“That’s not funny,” I imagine Robin saying. “We need to escape!”

I laugh again. It’s the morbid humor of the damned.

Control

The wound is, at first, a blessing. The night before the verdict, my little Oliver was pawing at me with an unusual desperation — even for him. A claw inadvertently leaves a small, bloody gash in my right armpit.

“Too much, Ollie,” I say, gently, while pulling him close.

Two days later, the mild pain in my arm brings a smile to my face, as I stare ahead at a concrete wall. The vision of my little boy is a blessing. But this blessing soon becomes a curse.

“It’s infected and spreading,” I say to the nurse, who drops by every morning for a five-second temperature check.

“I’ll send antibiotics,” she replies. Then she rushes off to the next cell.

I have no control over the wound or its treatment. It becomes inflamed and bright red. I wonder if it’s staph or MRSA, which I’ve seen eating away many animals in factory farms. The wound tears open from inflammation; blood spreads everywhere. I place a tight roll of toilet paper in my armpit to soak up all the red-yellow pus.

No antibiotics come. On day three of the infection, I ask the morning nurse (always a different person) again. She promises they will come within a day. But what comes instead is… a disposable heating bag. Then three straight 3:30am visits to deliver anti-allergy meds. I can tell from the staff’s faces and apologies that this is not due to incompetence or malice. They, too, suffer from a loss of control.

Connection

“I am resolute,” I tell myself. “I’ve been through hardship and isolation before.”

But as the days drag on, one word dispels my illusion of strength: Oliver.

For the past 7 years, our bond has been unbreakable. It was forged from fire and steel. Oliver was days away from the end: steel tongs would clamp his neck, a bloody blade would strike, and he would be dumped into boiling water over a fiery blaze.

Every other dog in Yulin was paralyzed by fear — crying or falling to the ground the moment a human appeared.

But Oliver jumped up towards me when I passed by. His ears were pressed against his head, and he had a nervous hope in his eyes.

“Please, sir, I’m hungry and afraid,” he said to me in the language of fear. “If you help me, I will love you for the rest of my life.”

And he lived up to the promise. For seven years — seven dark and difficult years — Oliver has been my best friend, my emotional guide… the light of my life.

There have been days when I have thought, everyone I love has been lost. My mom, who sacrificed everything to give her children a chance. Natalie, who gave me purpose when I was consumed by despair. Flash, my hero cat. Lisa, the killer who taught me lessons on love. And, just earlier this year, my little Joan, who showed me what it means to be brave. All gone. Forever.

But just a moment with Oliver casts all these shadows out.

“We’ll be together forever, dad!” he says as he happily paws and nuzzles and shakes his skinny bum. It is the language of love. “Together, forever! Promise me that will never change!”

And, upon writing those words, I burst into tears. I have not just been dislocated from the one being who loves me more than anyone in the world. I have broken my promise: that I would never leave him behind.

But then I collect myself and meditate. I see Oliver cuddling in the morning with his beautiful mom, Priya, and zooming around in her backyard with his brother, Beasley. I see my father, aged and diabetic, supported by my friends and family despite the imprisonment of his son; his voice cracks in gratitude for their grace.

And I see all the sentient beings of this earth with the ones they love. They are taken from the rusty cages and blood-stained kill floors to a place of care and light.

“It’ll be okay,” someone says to a poor creature, as she steps out of her cage, and into the sunlight. She looks up at her caretaker, first with curiosity then with something infinitely more powerful.

“You saved me,” she says. “I promise I will love you for the rest of my life.”

The promise is kept.

I wake from my meditation, and tears are streaming down my face again — but this time, tears of joy.

My dislocation is real. There is not a moment when I do not miss the ones I love. And, yet, exactly for that reason, perhaps, this isn’t the “wrong” place after all.

One cannot understand the urgency and power of light until one has lived in the dark. Perhaps, only by living with loss, will I truly understand the urgency and power of love.

UPDATE: Since I started this letter, I’ve been moved from “A” Block to “G.” I now have a pen and paper and can leave my cell 1 to 2 times per day, and for 60 to 90 minutes instead of 30. I am also now with a cellmate, a hard and angry Vietnamese man with a disfigured ankle from a gunshot wound. He has a good heart — he offers me food and advice — but his mind has been broken by this place.

He accuses me of lying, and lashes out when I scribble too loudly, or make too much noise by turning a book page. He has only a few rotten yellow teeth left, and seems jealous of my two rows of quasi-pearly whites. He cannot read or write in English, and barely speaks it. I’ve been helping him with the most basic requests — e.g., even a single Vietnamese book for him to pass the endless days.

Hi Wayne,

Can you please share your mailing address, and what kinds of things you’re allowed to receive? Books? Pens & paper? Vegan snacks? Chewing gum? Essential oils that can help you heal the infected wound and help boost your immune system? A blanket & pillow? A towel? A yoga mat? Cigarettes you can use to barter with other inmates?

Praying for your appeal process to move forward as expeditiously as possible.

Please let us know how we can make your life a little easier. Are you allowed visitors?

🙏 Kaci

You're an alchemist, Wayne. You will transmute base metal into gold and suffering into consciousness for our planet to move away from what has been rightfully described as the worst crime in the human history.