I Visited the FBI Agent Who Tried to Imprison Me. It was Great. (Podcast)

The government is not an ally to animal rights. But we can still use its actions as fuel for change.

I’ve done a lot of strange things as an activist. But among the strangest occurred earlier this month, when I visited the very FBI agent (Special Agent Chris Anderson) who spent the last 5 or so years of his life trying to imprison me for rescuing dying animals from factory farms. Days after I was acquitted, I went to the FBI’s southern Utah office to deliver an animal cruelty complaint to Anderson, alleging that Smithfield Foods was violating federal animal cruelty law. My lawyers told me that this was a very bad move because, well, this agent was not exactly my friend.

One of my attorneys wrote, “The FBI agent? Why in God’s name would you call the FBI?” (Much to her chagrin, I did not just call him. I went to his office for an in-person chat.) Another wrote, “I really want you to stay free” and “I fear the power of the FBI.” These were seasoned, long-time attorneys whose advice should typically be followed. And part of their prediction – that the FBI would take no action regarding our report, despite gruesome evidence of criminal conduct by Smithfield Foods – came true. When I spoke to Anderson, he expressed zero interest in enforcing animal cruelty laws against one of the largest and most powerful corporations in the state. (You can see the video of my visit here.)

But the scariest possibility – that the FBI would arrest me, perhaps on allegations that I violated the federal Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act – did not happen. This is not from lack of desire. Anderson testified at trial that at least 8 FBI agents were involved in the effort to prosecute me and my co-defendant Paul Darwin Picklesimer. Many other state and county officers, and prosecutors, were involved in the multi-state effort to criminalize our act of rescue. The government and FBI did not lack commitment in their effort to imprison us.

Rather, something else had changed in the dynamics at play at the FBI. And understanding what was actually happening on that day sheds light on a larger problem – government opposition to social change – but also how to solve it. It sheds light, in particular, on the fact that while we can’t trust the government to help animals (or create other social change), we can still harness the government, through popular opposition to its repressive tactics, to create change.

This is a dramatically different view than the one taken by most animal lawyers. As Justin points out, in his book Beyond Cages and his brilliant article in the Harvard Law Review, the traditional approach to animal rights has been, “Abuse an animal. Go to jail.” Animal advocates have seen the government, and its prosecutors, as allies in the fight against criminal animal cruelty. However, this alliance has mostly been an illusion. As Justin argues in Beyond Cages, while a few workers occasionally are arrested or deported for acts of extreme violence, the systemic cruelty at the heart of the system is left unaddressed.

Smithfield Foods’ continued usage of gestation crates, despite their public promises to the contrary, is one such example. When we reported this criminal cruelty to the authorities, they did not even bother to respond. This problem is not unique to Utah or gestation crates. In 2016, I and Priya Sawhney (among other team members) undertook a massive project to document and report criminal violations of a newly enacted ballot initiative, Prop 2, that prohibited extreme confinement at commercial agricultural facilities. We contacted every county in the state of California. Yet, despite clear evidence of corporate crimes, we could not identify a single investigation of violations of Prop 2, much less enforcement action, in the state’s history. (Read the report drafted by Leslie and Michael Goldberg to hear the full story.) This shows that the most extreme and widespread abuses are normalized, not challenged, by the prosecutorial establishment.

What can be done? Well, there are three important lessons the animal rights movement, and other movements, should learn from examples such as Prop 2, or Smithfield’s broken promise to phase out gestation crates.

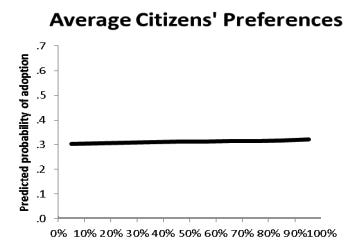

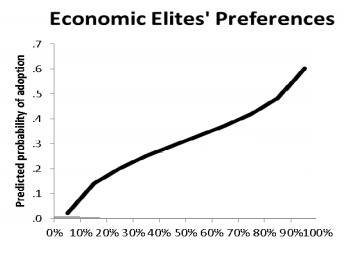

The first is that politicians (including prosecutors) listen to rich people, not you. This was, in fact, the provocative title of a report in Vox that summarizes research by Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern, showing that, on a wide range of policy issues, politicians ignore the concerns of ordinary people, but are highly sensitive to the concerns of the rich. Two charts tell the story.

The first chart shows the likelihood that a particular action is taken by politicians, as support from average citizens grows. The flat line shows that politicians essentially are unaffected by increasing support from the average Jane or Joe.

The second chart shows the likelihood that a particular action is taken by politicians, as support from the economic elite (defined by people in the top 10% of the income distribution) grows. The steep curve shows that politicians are highly motivated to take action, when rich people want it to happen.

Of course, Smithfield and WH Group (its parent company), with nearly $20 billion in assets, make even the richest Americans seem poor. The stranglehold the company has on our government, based in part on this extreme wealth, has been widely documented. I’ve called it corporate Stockholm Syndrome: entire communities that are held economically hostage by a corporation begin to defend its interests. Encouraging the government to take action against Smithfield, accordingly, is virtually impossible. In contrast, when Smithfield demands action – as it did very explicitly in our prosecution – then the government leaps to action.

The movement’s failure to recognize this essential point about American politics – that we can’t expect the government to be our ally, when it is controlled by wealthy corporations – has frustrated our efforts at social change.

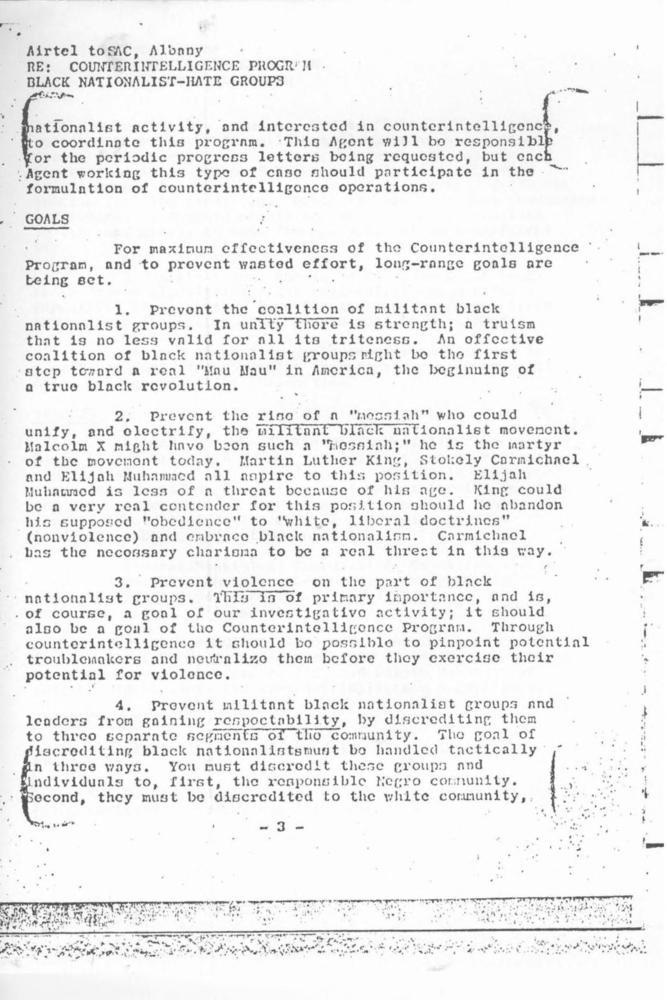

The second lesson is that, when powerful interests are threatened, the government will act to crush those who are seeking change. It’s not just that the government is unresponsive, in other words. It will actively seek to undermine movements, when they threaten the power structure of the status quo. Perhaps the most prominent historical example is the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program, aka COINTELPRO, which was deployed against civil rights activists in the 1960s. Despite horrific violence against nonviolent activists, including a firebombing of a bus of activists in Alabama and the murder of three activists in Mississippi, the FBI spent virtually no time trying to investigate civil rights violations. To the contrary, they fed information to local KKK members and police officers in their efforts to brutally repress the civil rights movement.

The goals of COINTELPRO were straightforward. Undermine unity in the movement, and attack its leadership. “In unity there is strength,” the FBI wrote at the time. The rise of leaders who could “unify, and electrify” a movement should therefore be stopped. Left unspoken was how any of this had to do with, well, law enforcement.

This same approach has been used by governments across the world in the face of efforts at social change. Vladimir Putin, for example, has engaged in extensive efforts to not just imprison his critics, but to smear them as Western puppets and traitors to Russia. The government of Saudi Arabia literally murdered a prominent journalist and dissident leader for daring to critique its leadership.

While there have not been state-sponsored killings of animal rights activists, there have been threats of violence by government officials in Utah. “You are going to be killed,” Sheriff Cameron Noel, of Beaver County, Utah, said to animal rights activists a few months ago. “And I won’t be there to stop it.”

The lesson from all of this is that repression is almost an inevitable part of social change. Indeed, that is why one of the leading global think tanks on nonviolent social movements has a manual on the subject. Far from expecting the government to support us, in short, movements must be ready for government attempts to destroy us.

That brings us to the third lesson, however: with popular support, we can make government repression backfire – and supercharge our efforts at systemic change. Michael Klarman, a professor at Harvard who is one of the leading scholars of social movements, has coined a term for this: the backlash thesis. The basic idea is that, while our direct efforts to change government actions often fail, we can harness the backlash against our efforts as fuel for popular mobilization – and social change.

The famous civil rights case, Brown v. Board of Education, is one such example. Klarman argues convincingly that Brown did relatively little to desegregate schools in the South. The case seemed destined, instead, to be mostly ignored. But then something changed after white Southerners began lashing out against Brown. The infamous image of angry white people shouting at black schoolgirl in Arkansas – one of the few examples of Brown having any impact – is one such example.

In the next decade, similar images of not just racists, but police officers attacking nonviolent civil rights activists shocked the conscience of the nation – and led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

The lesson for animal rights activists is that, while government may not be our ally, we can use government repression to fuel our efforts at change. That is precisely what happened in the Smithfield trial. I am not a particularly famous or influential person, yet the most important newspaper in the country published an article by me – making a strong case not just for animal welfare but animal rights – as a result of the government’s efforts to put me in prison. One Oxford scholar has called it the power of “communicative suffering” (but I prefer the term “unearned suffering.”) The idea is the same: there is great power in voluntarily exposing ourselves to suffering, and even persecution, in generating support for a movement.

The irony of this, of course, is that it turns out the government does have a crucial role in driving social change. But not because it will listen to our policy demands; Gilens’ and Page’s research shows that the concerns of average citizens have little impact on government. And not because it will prosecute animal cruelty; far from it, the government is much more likely to prosecute activists than corporate abusers. No, government’s key role in social change is as a foil – a villainous contrast to a nonviolent movement that is simply trying to make the world a kinder place.

The government’s attempt to put Paul and I in prison, for merely taking two sick and dying piglets to receive emergency care, is the most powerful recent example of how this works. But it won’t be the last. And that is part of the reason why I was not afraid to visit the FBI, days after a jury acquitted us of all charges. I knew that, even if I was arrested, and prosecuted for another crime, our movement could use the prosecution as fuel for more change.

And that includes even the FBI agent himself. I have promised not to divulge the specific details of that conversation with the public. And, in many ways, it was frustrating – like an example of Gilens’ and Page’s research on the powerlessness of average citizens, and the power of corporate influence, come to life.

But what I can say is this: even the prosecutors and FBI agents involved in these cases cannot come out of them unchanged. Perhaps it’s just a recognition that ordinary people, even in conservative regions of the country, will not imprison people for acts of compassion towards suffering animals. Perhaps it’s an appreciation of the professional consequences of pushing a years-long investigation and prosecution, only to have the entire corrupt enterprise end in failure: the activists walking free. But I have reason to think that, even for those who sought to put us in prison, part of what has changed is a new understanding of animal rescue and animal rights.

“If you make the right choice…. maybe, just maybe, a little piglet like Lily won’t have to starve to death on the floor of a factory farm.” I meant to issue that moral challenge to the jury (and they came through with flying colors). But after meeting with Agent Anderson, and witnessing the changed tone in his voice, the softening expression on his face, I knew that he – and the entire prosecutorial establishment of the United State government – had been challenged too. I hope and expect, someday, they will make the right choice, too.

These days I think it’s often up to individuals to directly help the animals, people, and Earth.... Especially when in the U.S. the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act of 2006 and ag-gag laws in many states have hindered animal advocacy organizations. Signing online petitions, bearing witness, peddling “awareness” merchandise, and other obsolete tactics have taken the teeth out of these groups, and then there are the “panhandlers” from corporate animal advocacy organizations. Global corporations rule the world, with governments increasingly as an extension of that dominance. So it’s up to citizens to take action on our own, guided by our conscience and using the skills and means that we each have to be of practical help to anyone who needs it.

Yes we took practical action on our own, protesting against a local fast food joint in chicken costumes for two years (they closed, I got severe skin cancer); then protested against a local fur store for a year and a half. They closed, hurray, but the AETA as well as tort limits barring suits against corporations really took hold then. Now, thanks to Wayne and brave company, I'll help again any way I can (Don't press for $, as I donated half my lifetime income to animal rights and am - temporarily I hope - skint.) With love from Vegans in Oregon!