The Reverse Panopticon

How jails and factory farms reveal society’s hidden evils.

“If a race war breaks out, you fight.”

The Keyholder of the Others in jail offered me these words, as both advice and warning. The Others – mostly Asians but also including anyone else who was not clearly white, Black, or Latino – were hardly a force to be reckoned with. Our group included an elderly Vietnamese man with a gunshot wound that had disfigured his right ankle. A middle-aged Laotian who found God in jail and spent much of his time reading the Bible. And me, a bookish Chinese guy who was training inmates to meditate, not fight to the death.

But the Keyholder, the individual designated as leader of the Others, wanted us to be prepared. And that required understanding the color code: we stuck with those in our race, even if that meant using deadly force in a race fight.

Explicit racial segregation was just one of many ways, however, that my experience in jail demonstrated the hidden evils of our society. From mind-boggling hypocrisy to disturbing levels of waste, jails shine light on how power is abused.

In this regard, places of incarceration experience a curious reversal of function. Modern jails are inspired in part by an 18th century architectural design called the panopticon (Greek for “all seeing”), which was meant to be a place of perfect surveillance of “bad people.” But, if you look closely, jails also serve as perfect reflections of “bad power.” They are like a mirror that reflects our nation’s greatest evils, a reverse panopticon that exposes, not the bad things that inmates do, but the bad things (like racist violence) that those in power would prefer to hide.

There is another place where this reverse panopticon is realized in even truer form: the factory farm. And it behooves all of us, not just animal advocates, to look at the panopticon’s mirror. Because when we look, we may see that this power can be used against us, too.

Entering the Panopticon

Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon was intended to perfect the exercise of power. A single anonymous tower was in the middle of the design, with cells constructed in a circle around it. The goal was to have complete surveillance, and therefore control, over all the inhabitants. Bentham intended for this design to be a humane alternative to the more brutal forms of control exercised by the state at the time, such as the drawing-and-quartering of Robert-François Damiens, who was convicted in 1757 of attempting to assassinate the King of France. Damiens reportedly cried out, “O death, why art thou so long in coming?” as he was slowly torn to pieces.

The modern Panopticon – whether a jail or factory farm – has taken Bentham’s design into its most extreme form. Every act you take in jail, including using the bathroom or taking a shower, is visible to the jail staff. Indeed, the first step of being housed in jail is a strip search in which one has to bend over and spread one’s butt cheeks, allowing a guard to see fully up your asshole. Similarly, every biological function in a factory farm is observed and controlled, down to the number of functioning teats on a mother pig.

Contrary to Bentham’s original design, however, the transparency of modern panopticons does not go both ways. While the government is allowed to literally see up an inmate’s ass, no one is allowed to see what the government does. Access to the facility is strictly limited, with only a few short visits allowed every week. And no one records what happens inside; even lawyers are not permitted cell phones when they meet with inmates in jail.

The factory farming industry, of course, takes even more draconian measures. It has turned the act of documentation into a crime.

The result of this perfect anti-transparency is that the darkest aspects of our society can rear their heads. And that starts with race. In the jail or factory farm, racism is not just alive and well. It has been perfected by those in power.

Jim Crow never died

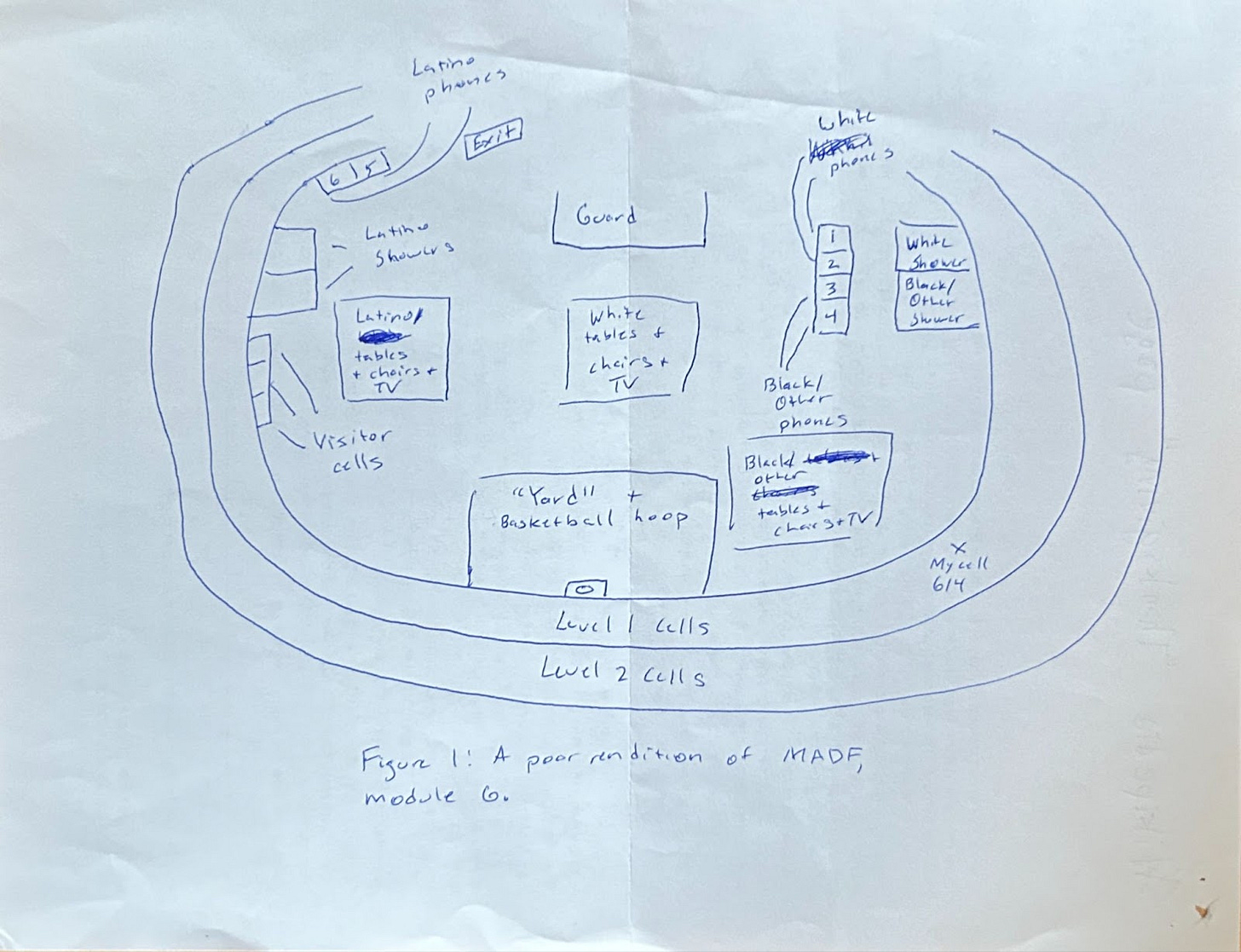

Jail and factory farms are perhaps the last bastions of state-mandated racial segregation in America. In everything from housing to phones and showers, there is a strict color code — and a violation can have violent consequences.

For me, racism was most obvious in the fight for the phones. Every day, when we were released from our cells, people would rush to make a call. We had, at most, 15 minutes to reach our friends, family, and even our lawyers. But, as an Other, there were no phones clearly designated for my racial group. I found myself repeatedly kicked off the phones after 5 minutes or less, especially when there were white people behind me in line. This is all done in full view of the jail staff, who stand a few feet away at the guard desk.

The racial segregation of jail, however, pales in comparison to the racism that has unfolded in modern factory farms. Indeed, there have been numerous instances of literal slavery at the largest livestock corporations in the world.

Take Circle Four Farms, the Smithfield facility that I was charged with burglarizing in a trial that ended with my acquittal in October 2022. One of the many facts that the court banned us from discussing was that the company had been shipping workers in from Asia, then forcing them to work without pay. Only when these desperate workers left the facility to search for pay phones and call for help was the scheme exposed. Ironically, on at least one occasion when local police saw Asian workers walking away from the farm, they pulled guns out and accused them of being terrorists or illegal immigrants. It never occurred to those officers that it was the company, and not the slaves, who had committed crimes.

It should come as no surprise that scenes like this unfold in jails and factory farms. They are places where “Others” – including animals – are routinely treated with violence. A little racism at the phones, by comparison, starts feeling like kindness.

The Hypocrisy of the Rule of Law

Prosecutors and judges love to talk about the rule of law to justify their punitive actions. Indeed, this was central to prosecutor Robert Waner’s closing argument in my trial. You may sympathize with his beliefs, Waner said, but society will descend into chaos if people like Wayne don’t follow the rules. Yet the panopticon shows how the “rule of law” really applies only to those who have no power. Powerful institutions routinely violate the rules – and face no accountability at all.

Take, for example, the rules in jail. Inmates are told from Day 1 that even the mildest infraction – a hole in one’s sock – can lead to severe punishment. Damaging a sock, the rulebook explains, constitutes criminal mischief and can lead to solitary confinement or further criminal charges.

But while inmates are punished for mild infractions, far more important rules are routinely violated by those in power. For example, the attorney-client privilege – which requires that conversations with attorneys be held confidential – is one of the most ancient and sacrosanct rules of the American and English legal systems. But even after weeks of requesting confidentiality, my phone calls were still recorded by the state. Every call I made started with the same recorded message: “This call is being recorded by Global Tel Link.” I reported my concern. No one seemed to care.

Another rule, embedded in the US Constitution’s Sixth Amendment, permits any defendant to represent themselves and receive resources necessary for undertaking that self-representation, e.g., statutes and case law, materials to prepare legal filings, and the right to contact witnesses outside of jail. But, despite my numerous requests, the jail failed to provide me any materials promised for self-represented parties, or any meaningful time to contact witnesses on the phones. Indeed, the jail’s only response to my requests for legal resources was to say they did not have me listed as representing myself. I protested they had this wrong. No one ever replied.

Worst of all, the jail provided many crucial legal filings – such as probation’s pre-sentencing report and the prosecution’s statement of facts – after 10:30 pm on the night before I was supposed to challenge them in court. At that point, just hours before my appearance, it was too late for me to prepare any meaningful response – or even read the documents being used against me – before the jail went dark. So much for the rule of law.

The lesson one learns in jail is that rules apply only to those who lack power. Powerful institutions, such as the government, can routinely violate the rules, even those set out by the US Constitution, and face zero accountability.

This is even more true of factory farms. Take, for example, the rules against intensively confining animals in the state of California. Prop 2 went into effect in January 2015 and made unlawful the use of so-called battery cages in California. Yet powerful corporations have violated it with impunity.

I’ve worked with one of the leading animal lawyers in the nation, Carter Dillard, the former director of litigation of the Animal Legal Defense Fund, and we have not been able to find evidence of even a single successful prosecution in the 8 years since the law went into effect. The government would like us to believe that, out of the tens of millions of hens who have suffered confinement since 2015, not one has been treated unlawfully.

That result is statistically preposterous. Tens of millions of hens have lived and died in this state since 2015, and no industry has a 100% compliance rate. (It would be more plausible to say that there has been no crime in San Francisco, a city of 800,000, in the last year.) The industry’s supposedly-perfect record, however, is also clearly contradicted by the evidence. For years, we submitted to the authorities clear evidence showing that Sunrise Farms, among other facilities, was breaking the law. See, for example, the clip below, shot in 2016, which shows thousands of hens confined in battery cages.

But the authorities refused to enforce the rules against a powerful company — or even look at our evidence. They prosecuted us instead. At my trial, the owner of the company, Mike Weber, lied under oath repeatedly and claimed his facility had no battery cages and was complying with the law. That lie, like the unlawful confinement of hens itself, was a crime. Making false statements under oath is felony perjury, punishable by up to 4 years in prison. But in the factory farming industry, breaking the rules matters only if you are someone – a worker, an activist, or an animal – who has no power.

Waste as a way of life

Those in power love to describe the suffering within the panopticon as a necessary evil. “If only criminals behaved, we would not have to punish them in prisons and jails,” they say. “If only we could survive without eating animals, we would not have to torture them in factory farms,” they add. What they fail to point out is that most of the abuses in the panopticon have no purpose. Waste is a way of life.

Take, for example, the medical negligence in jail. One week after I finally received some treatment for a festering wound on my arm, medical staff came to check in on me again.

“We have your dentures,” they explained, showing me a blue-green box and a bag of cleaning chemicals. I looked at them flabbergasted. It was the sixth time in two weeks that I had been brought medication or supplies — allergy medications, heating pads, etc. — I did not need.

My experience was not unique. My cellmate was experiencing stabbing pains in his chest that he thought might be a heart attack; the doctor promised by a nurse never came, but they did bring him ibuprofen which he promptly threw away. Another inmate had back pain so severe that it was inhibiting his ability to walk; when the nurse finally came, she offered him a blood test and nothing for his back.

The wasted resources in medical care are, sadly, par for the course in jail. The food was terrible – for me, 107 straight meals of peanut butter sandwiches – and much of it appears to be thrown away. Enormous amounts of mail, the inmates’ primary link to the outside world, ended up in the garbage for the silliest of reasons – e.g., “stains” on the envelope, or the use of “colored paper.” And an entire multimillion-dollar jail called North County Detention Facility (NCDF) – that went through a $1.8 million kitchen renovation in 2021 – is completely empty of inmates, despite overcrowding in the Sonoma jails. The county has apparently blamed this waste of millions of dollars on staffing shortages.

The biggest source of waste, however, is with the inmates’ connections to the world. Visits from friends and family are limited to a maximum of 30 minutes, 3 times a week, through a plated glass window that makes it very difficult to hear what your visitor is saying. Lockdowns constantly cancel these visits. My father drove 3+ hours to visit me one weekend only to be told 5 minutes before he was to see me that our meeting – our first chance to see each other since I was jailed – would be canceled. Loneliness kills, and jail is slowly killing people by depriving them of evolution’s primordial bond: the connection to those we love. It should come as no surprise that the United States has a shocking 70% recidivism rate, compared with 20% in Norway, a country that allows inmates to leave jail to visit their loved ones. People who are broken and disconnected have no reason to obey the laws.

But the waste in jail pales in comparison to the waste that happens in factory farms. The Humane League points out that 26% of all farmed animals are disposed of before reaching the consumer, due to a variety of factors ranging from infectious diseases to incompetence. Those 26% of animals (approximately 14 billion in the United States so far this year) did not lose their lives to fill someone’s belly. Their lives were simply thrown away.

The routine disposal of living beings, as a waste product of Big Ag, is the tip of the iceberg. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 77% of the agricultural land on this planet is being used in meat production, which creates only 18% of the calories humans consume. A recent study in Nature Sustainability found that 56% of the water in the Colorado River basin – the most important drinking water source in the Western United States – is being used by the livestock industry, which has received extensive subsidies while ordinary people have faced crippling water surcharges. The largest water reservoir in the nation, Lake Mead, is going completely dry.

But as with the humans in jail, the greatest waste stems from the love that could have been – but was lost. I’ve written previously about the social bonds that provide immense meaning to farm animals, and the profound suffering they experience when those bonds are broken. Unlike inmates in jail, these animals aren’t just separated from their families. They’re never given families at all. The decimation of their emotional lives – to fill the pockets of billionaires like Smithfield owner Wan Long – is not just a waste. It is, in the words of the renowned philosopher and futurist Yuval Noah Harari, one of the worst crimes in history.

Through the reverse panopticon

The evils of the panopticon, however, are not just a projection but a prediction. What happens in the privacy of the halls of power, to those who are most vulnerable, can happen to us all. This is why it should come as no surprise that the racism, hypocrisy, and waste that occur in factory farms are also inflicted on human beings in jails. Abuse of power never contains itself to one cage.

And, increasingly, we are all in a cage: financial, political, and even psychological. Forty percent of Americans cannot pay an unexpected $400 bill. Dissent from the political party line is met with punishment, ostracism, or even death. And perhaps most terrifying is the prison of our minds: Millions of people, suffering in the pandemic of loneliness, are trapped by a world where no one seems to care.

There is hope, however, even in the panopticon. Indeed, when we see how our system is imprisoning us all, we can escape the institution’s cage. The reverse panopticon is not just a tool of transparency. It’s a path to liberation. When we see the panopticon’s walls, we can start to understand the strategies we must take to escape.

But for that argument to be developed, we’ll have to wait for the next blog. In the meantime, our tour of the panopticon has come to an end. I hope you enjoyed your stay.

A theme to me here is that transparency makes us mindful of our behavior, and the lack of it enables our worst behavior.

The panopticon metaphor is fascinating and dovetails very well with the urgency of open rescue. We have to give the public the right to know about what happens in factory farms. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

Thanks, Wayne. You connect the dots well. I hope your essays are read by more and more people. I hope you get them translated into other languages too.