What We Can Learn from AI Research

We are not nearly as smart as we think. But we can get smarter, if we develop the general capacities to learn.

I spoke to Kirsty Henderson today, the President of Anima International in Europe. And I was struck by the general nature of her organization’s strategy. They do not have any particular campaign or tactic. Rather, they focus on building a strong culture, grounded in radical candor, and a general organizational infrastructure that allows talent and intelligence to adapt to new circumstances. This reminded me of something called The Bitter Lesson.

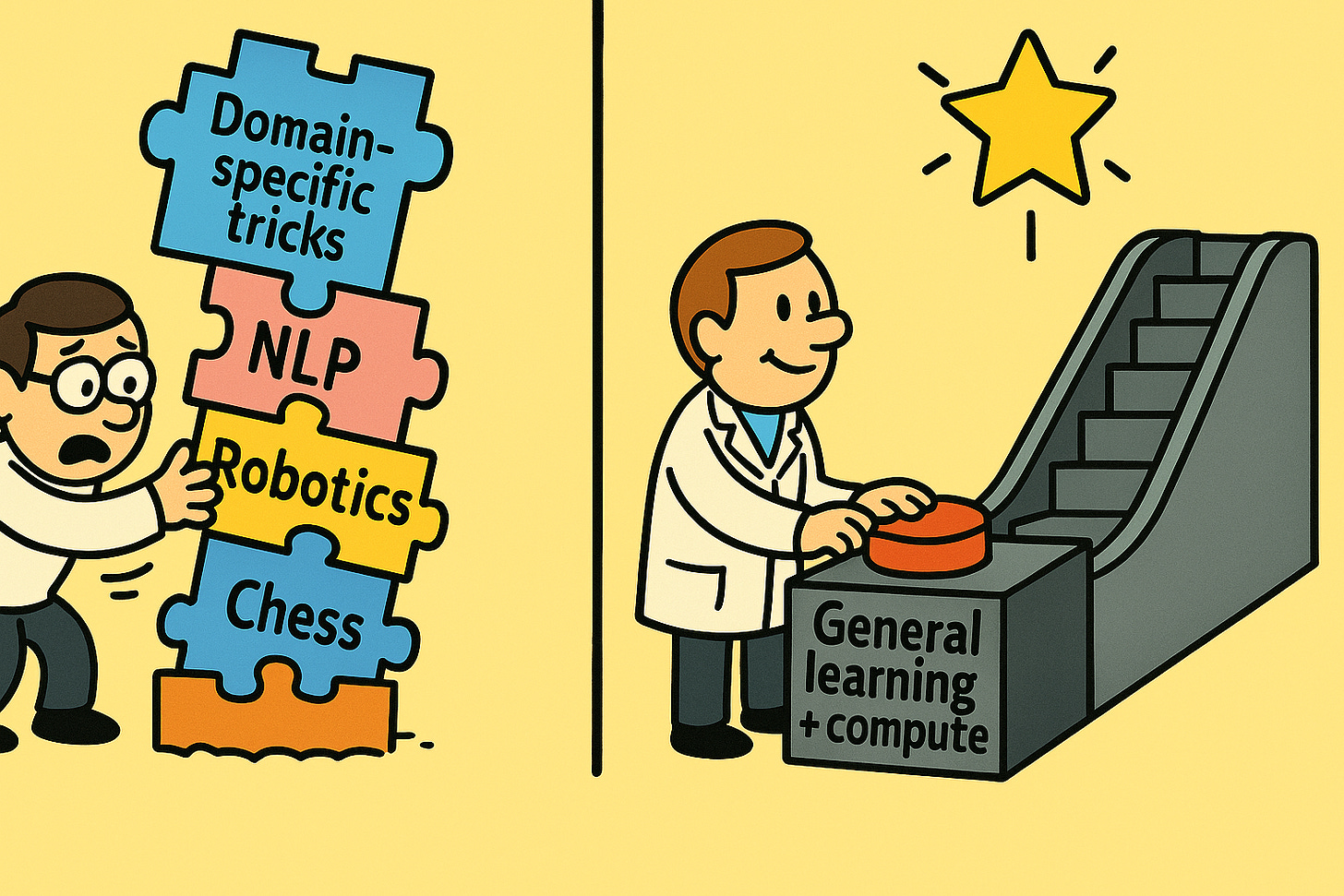

The Bitter Lesson is among the most important essays in the (short) history of artificial intelligence — but it can just as easily be applied to animal rights and other causes. In essence, the lesson is this: general capacities — particularly ones that have the ability to scale, such as learning and search — are far more important than specific tactics for achieving long term success. And the difference is large, partly because Moore’s Law (i.e., computational power doubles every two years due to technological progress) makes general capacities such as learning and search vastly more effective over time — but won’t improve specific tactics.

That is a bitter lesson because each of us, as individuals and organizations, is attached to our specific tactics. We believe we’ve figured something out: about investigations, or outreach, or lobbying, or corporate campaigns, or some other specific tactic.

But this leads to two major problems. First, we cannot adapt when the lessons from our specific tactic no longer apply. Our activism has become “overfitted” to a small set of scenarios. As Anima’s Jan Sorgenfrei has put it, we are climbing the wrong hill.

Second, we lose out on the opportunity to improve our meta-level capacities — e.g., learning and exploration — by focusing too much on the specific tactic. For example, if we focus too much of a cage-free campaign on “winning,” and not enough on “learning,” then that may ironically compromise our ability to “win” over the long term. This is because, across a wider set of challenges, learning is our most powerful tool for winning! This is what happens when organizations robotically apply best practices without developing tools for their teams to learn from those practices — or, better yet, challenge them when better approaches become apparent.

Indeed, the narrow focus on optimizing for a specific tactic, in the long run, may even limit progress on that specific tactic. This is because, when we focus too much on “winning” with a specific tactic, rather than meta-level capacities like learning and exploration, we miss out on deeper insights. We become too obsessed with the things we already know, and not nearly obsessed enough on the more fundamental truths that we could discover if we were willing to learn.

In other words, the Bitter Lesson is that we are not as smart as we think we are, which is why it’s always most important to focus on learning and exploring rather than on deploying the latest trick. This is especially true when society has massively improved our individual and collective ability to learn and explore, partly due to Moore’s Law. Moore’s Law is, in a sense, a floor on our collective ability to compute. (After all, we control the chips of Moore’s Law. So when their compute improves, so does ours!) That means the Bitter Lesson may apply even more to human social intelligence than the intelligence of machines.

I’ve seen the Bitter Lesson play out many times in my own activism. In my earliest years, I overfit on leafleting, and, though I became an incredibly good leafleter, my skill with leafleting became irrelevant when I moved on to doing investigative and rescue work. (There’s no one to leaflet when you’re sneaking around in the middle of the night!)

Later, when I moved to grassroots work, I overfit on disruption, and I encoded in our work too many of the best practices for disrupting, rather than the more general techniques (community building, leadership development) that would be more effective and enduring at scale.

And my latest error was overfitting on open rescue. The strategy has been immensely successful, but it runs into natural bottlenecks if the underlying organizational platform isn’t built to optimize for learning and exploration. The people we recruit for open rescue, and the organizations we create, often need to develop more general capacities before they can successfully operate effectively even within that specific tactic.

It is a bitter lesson. But one I hope that I learn — and the movement learns — so we seize the power of collective intelligence to solve the greatest problem of them all: the suffering of sentient beings.

This reminds me of what'd happened at the NASA data center where I'd worked for many years, when the Science Group, originally organized as largely independent "data support teams," was reorganized to largely top-down-managed, discipline-based, internal centers (e.g., one on precipitation). The creativity, productivity, camaraderie, and morale that had gushed became a trickle within an incredibly short period of time, especially camaraderie and morale (e.g., sharing became withholding). The same group of people, but now organized differently. Changes in subsequent years led to some improvements, but that gushing dynamic never came back.

One of the best lessons I learned there: structure determines behavior.

I understand that specific tactics may become overfitted and have a short lifespan, but isn't repeatedly carrying out an action that has proven to be effective and attracts the attention of the media until it doesn't a needed win to keep the pressure on and proclaim we mean business?